Welcome to the educational program Nutrition. This program will discuss some basic principles of proper nutrition and hydration for the elderly and help you identify some of the challenges with eating and drinking that often develop in the later stages of dementia. It will also provide some guidelines and strategies for supporting good nutrition and hydration in those with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

. . .

This is Lesson 28 of The Alzheimer’s Caregiver. You may view the topics in order as presented, or click on any topic listed in the main menu to be taken to that section.

We hope that you enjoy this program and find it useful in helping both yourself and those you care for. There are no easy answers when it comes to the care of another, as every situation and person is different. In addition, every caregiver comes with different experiences, skills, and attitudes about caregiving. Our hope is to offer you useful information and guidelines for caring for someone with dementia, but these guidelines will need to be adjusted to suit your own individual needs. Remember that your life experiences, your compassion and your inventiveness will go a long way toward enabling you to provide quality care.

Let’s get started.

Prefer to listen to this lesson? Click the Play button on the playlist below to begin.

Proper Nutrition

Regardless of the stage of Alzheimer’s disease, every individual needs proper nutrition to maintain good health. This often becomes a challenge in the later stages of Alzheimer’s when appetite decreases, metabolism declines, and the ability to eat and drink independently deteriorates. Weight loss often occurs, so people with dementia need a diet consisting of foods high in nutritional value, referred to as “nutrition-dense foods.” They should have a well-balanced diet of fruits, vegetables, dairy, meats and whole grains, while recognizing allergies and dietary restrictions, such as salt. The DASH diet is an “Eating Plan” originally developed for persons with high blood pressure, but it is an overall nutritionally dense food diet with all the essential elements. More information on the DASH diet can be found at the website link provided.

Regardless of the stage of Alzheimer’s disease, every individual needs proper nutrition to maintain good health. This often becomes a challenge in the later stages of Alzheimer’s when appetite decreases, metabolism declines, and the ability to eat and drink independently deteriorates. Weight loss often occurs, so people with dementia need a diet consisting of foods high in nutritional value, referred to as “nutrition-dense foods.” They should have a well-balanced diet of fruits, vegetables, dairy, meats and whole grains, while recognizing allergies and dietary restrictions, such as salt. The DASH diet is an “Eating Plan” originally developed for persons with high blood pressure, but it is an overall nutritionally dense food diet with all the essential elements. More information on the DASH diet can be found at the website link provided.

Food also needs to be prepared and served to address the person’s level of functioning and oral or dental needs. Food items should be easy to chew and swallow, with a low risk for choking. This generally means that food should be soft and cut into small portions or pureed. Thick liquids are also easier to swallow and generally safer than thin liquids, which can easily go down the wrong way in the throat. Therefore soups and other liquids should be thickened with thickening agents when swallowing difficulties develop. Some signs of swallowing difficulties include spitting out food, coughing or choking while eating or drinking, or lung infections due to inhaling liquid or food particles. We will discuss more about swallowing difficulties later in the program.

Click here for more information on the DASH Eating Plan.

Brain Healthy Nutrition

Good nutrition is important not only for good physical health, but also for helping slow the progression of memory loss and dementia. With aging, the body accumulates damage to cells due to inflammation and oxidative stress (damage caused by a form of oxygen). As this damage accumulates in the brain, brain cells die or lose the ability to function properly, which contributes to brain aging and diseases such as dementia. Studies suggest that eating “brain healthy” foods, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, olive oil and fish, may counteract some of these effects and improve mental function and slow down brain aging. On other hand, inadequate intake of vitamins and minerals, including magnesium, zinc, iron, vitamin D, calcium, and selenium, have been associated with DNA damage and cellular aging.

Good nutrition is important not only for good physical health, but also for helping slow the progression of memory loss and dementia. With aging, the body accumulates damage to cells due to inflammation and oxidative stress (damage caused by a form of oxygen). As this damage accumulates in the brain, brain cells die or lose the ability to function properly, which contributes to brain aging and diseases such as dementia. Studies suggest that eating “brain healthy” foods, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, olive oil and fish, may counteract some of these effects and improve mental function and slow down brain aging. On other hand, inadequate intake of vitamins and minerals, including magnesium, zinc, iron, vitamin D, calcium, and selenium, have been associated with DNA damage and cellular aging.

Foods rich in antioxidants (or substances that counteract oxidative stress), folate, vitamins B6 and B12, and unsaturated fatty acids, such as omega-3 fatty acid, improve brain health, mental function, and memory. The most abundant antioxidants in food are called polyphenols, which appear to counter brain aging and degenerative diseases, such as dementia, heart disease and cancer. Foods high in polyphenols include certain fruits, vegetables (particularly spinach), nuts (particularly walnuts), whole grain cereals, chocolate, tea, coffee, and red wine. Blueberries and blueberry extracts are especially rich in polyphenols. So a brain healthy diet should include regular servings of fruits, vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acid, found in fish and olive oil.

Taking antioxidant supplements can also slow brain degeneration. A combination of supplements, such as vitamins E and C, appears to be more effective than taking a single supplement. In fact, the most convincing evidence suggests that a variety of antioxidants (in the form of a nutritious diet and supplements) combined with behavioral enrichment (involving physical, social, and cognitive components) is most effective in improving mental function and reducing brain degeneration.

Healthy Diet and Lifestyle

The best approach for improving mental function and delaying age-related diseases is to exercise, maintain a lean, healthy body weight, and follow a diet low in saturated fat but high in fruits, vegetables, wholegrain cereals, and other sources of antioxidants.

Physical exercise promotes overall health in many ways. It improves memory and mental function, most likely by increasing blood circulation to the brain. It elevates mood and energy, which can improve motivation and effort in task performance. Exercise also helps maintain a healthier body weight and lowers the risk of many chronic health problems, including heart and lung disease, which in turn lowers the risk of dementia.

As people age, caloric needs typically decrease but nutritional needs remain high. For older adults, it is best to eat nutrient-dense, well-balanced meals containing a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, lean meats, poultry, and low-fat dairy products low in cholesterol and saturated and trans fats. Foods that are high in fat, sugar, and salt, such as processed foods should be avoided. Healthy snacks are also an important source of nutrition, especially in the later stages of Alzheimer’s when weight loss is a problem. Foods high in fiber, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and beans are also important for preventing constipation.

As people age, caloric needs typically decrease but nutritional needs remain high. For older adults, it is best to eat nutrient-dense, well-balanced meals containing a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish, lean meats, poultry, and low-fat dairy products low in cholesterol and saturated and trans fats. Foods that are high in fat, sugar, and salt, such as processed foods should be avoided. Healthy snacks are also an important source of nutrition, especially in the later stages of Alzheimer’s when weight loss is a problem. Foods high in fiber, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and beans are also important for preventing constipation.

Because vitamin and mineral deficiencies are common among the elderly, vitamin supplements that include folic acid, calcium, vitamins D, B6, B12, C and E should be considered and discussed with a physician.

In the later stages of dementia, unhealthy weight loss is common. A physician and dietician should be consulted to evaluate for underlying causes, treatments, and nutritional supplements.

To learn about a modified food pyramid for older adults, please go to the provided link.

Hydration

Proper hydration is very important for good health. Elderly people are more prone to dehydration, because they have less water reserve in their bodies, a decreased thirst trigger, and the kidneys are less efficient at keeping water in the body. Swallowing problems, poor food intake, and long periods between drinking fluids can increase the risk of dehydration. Some elderly may also be taking medications (such as diuretics or laxatives) that increase fluid loss. Some people may also be reluctant to drink, because drinking will increase their need to use the toilet or increase their risk of incontinence.

Proper hydration is very important for good health. Elderly people are more prone to dehydration, because they have less water reserve in their bodies, a decreased thirst trigger, and the kidneys are less efficient at keeping water in the body. Swallowing problems, poor food intake, and long periods between drinking fluids can increase the risk of dehydration. Some elderly may also be taking medications (such as diuretics or laxatives) that increase fluid loss. Some people may also be reluctant to drink, because drinking will increase their need to use the toilet or increase their risk of incontinence.

In late and end-stage Alzheimer’s, incontinence is unavoidable. Some elders may cut down on their fluid intake to prevent having to get up in the middle of the night to use the toilet. It is true that many falls with hip and shoulder fractures occur at night when an elder tries to get out of bed to use the toilet without asking for help. The risk of falls is often increased by poor lighting and hazards along the path to the bathroom. The fall risk can be reduced with proper lighting and assistance getting to and from the toilet.

Older people are also at greater risk for the health problems associated with dehydration, including urinary tract infections, constipation, confusion, dizziness, and kidney and heart problems.

For all of these reasons, the elderly, particularly those with dementia, must be encouraged to drink. The Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Council recommended approximately 1 milliliter of water for each calorie of food, which would amount to roughly 64 to 80 ounces of water a day for average adults. Keep in mind that most of this water is taken in through the foods that we eat, so the recommendation does not mean that you should drink that much free water a day.

Proper Hydration

Here are some guidelines and strategies for ensuring proper hydration.

Offer water or other drink every 2 hours. Set a daily schedule for drinking as well as eating. Identify key times during the day that offering a drink fits naturally into other types of activities. For example, before and after taking a walk, sitting down to watch a movie, or enjoying an afternoon on the back porch are all times that offering fluids makes sense. Having a drink with every meal and offering drink breaks throughout the day can help to compensate for the lack of feeling thirsty. Drinking is a social behavior, so try to sit down and have a nourishing drink with your care recipient. The person may model your behavior and take a drink.

Keep a glass or bottle of water near a favorite chair or in the car to remind the person to drink more often. If the person tends to wander during the day, try offering fluids with in a cup with a lid so that she or he can continue to walk but may be cued to take a drink from time to time. If the individual likes coffee or tea, that preference should be honored, but juices and water should be encouraged as alternatives. Caffeinated drinks should be minimized or avoided and restricted to morning hours if possible. Drinks that are too cold may be uncomfortable, so serve a drink that is slightly cooler than room temperature, but not icy cold.

Proper Hydration (Continued)

Offer a small cookie or cracker as an incentive to drink a glass of water or juice. Try adding new flavors to drinks by splashing some fruit juice, a lemon slice, or sliced cucumber to a glass of water. Try serving a flavored, decaffeinated tea. You can also try adding other sources of water to the diet, such as fruit ices, popsicles, and gelatin desserts.

Treat yourself and your care recipient to a milk shake or root beer float as a special activity that is fun and also provides a good source of additional hydration.

The World Health Organization (or WHO) developed a drink containing sugars and salts to improve absorption and prevent dehydration. This drink can be prepared at home by mixing:

- 3/4 teaspoon table salt

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 4 tablespoons sugar

- 1 cup orange juice in

- 1 quart or liter of water

Individuals with dementia should be weighed at least weekly to determine if they are maintaining their weight.

Individuals with dementia should be weighed at least weekly to determine if they are maintaining their weight.

Sometimes difficulty drinking or swallowing is caused by a treatable medical issue. If the problem persists, or if there are signs of dehydration (such as dry mouth, nose, and skin, light-headedness, low energy, fainting, and low blood pressure), consult a physician.

Encouragement, patience and cueing are the keys to keeping someone with Alzheimer’s disease eating and drinking. It may only be a few bites and a few sips at a time, but being patient and continuing to try new strategies will pay off!

Case Study 1

Let’s look at a cast study with 72-year-old Robert, who is now in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Robert’s awareness of his environment has diminished considerably. He barely looks at his food and makes no effort to pick up a fork or cup.

In this situation, Mary, the caregiver, attempted to assist Robert with his meal.

What was wrong with Mary’s approach to assisting Robert with his meal?

- A. Mary failed to get Robert’s attention and engage him.

- B. Mary failed to notice that Robert was not aware of his surroundings and not focused on the task of eating.

- C. Mary wrongly assumed that Robert had the abilities to chew and swallow.

- D. Mary endangered Robert by not staying with him to make sure that he did not choke on the piece of chicken.

- E. All of the above.

Case Study 1 Answers:

Choice A: “Mary failed to get Robert’s attention and engage him” is a good choice.

People with dementia lose the ability to pay attention to their surroundings and concentrate on a task. In the later stages of dementia, these losses are profound, so caregivers will need to make considerable effort to focus their care recipients on tasks such as eating. In order to get Robert’s attention, Mary needs to sit near him, get close, make eye contact, and say his name. Taking his hand can also be helpful in getting his attention.

Choice B: “Mary failed to notice that Robert was not aware of his surroundings and not focused on the task of eating” is also a good choice.

Mary didn’t tune into Robert’s non-verbal message that he was not in touch with his environment and that he was not aware of sitting at a table with a plate of food that he should eat.

Carefully observing people’s facial expressions, gestures, posture, and state of dress (whether neat or disheveled) can give much information about their emotional and mental states. In this situation, Robert’s facial muscles were loose, mouth slightly open. He had no expression, though his eyes were open. He was slumped in the chair in what appeared to be an uncomfortable position, though he did not protest.

If Mary had used her powers of observation, she first would have assured herself that Robert was breathing, then would have realized that he had very limited mental activity at the moment and was not aware that he was supposed to be eating.

By the late stages of Alzheimer’s, there has been significant damage to the parts of the brain that control appetite and thirst. The usual signals that tell people that they are hungry or thirsty are not working properly. They may sit looking at the food, even playing with it, without recognizing that they are hungry or that they are supposed to eat.

Choice C: “Mary wrongly assumed that Robert had the abilities to chew and swallow” is another good choice.

In the later stages of dementia, the abilities to chew and swallow diminish and are eventually lost. This is referred to as “feeding apraxia,” a loss of the automatic self-feeding skills people learn during childhood.

Some capacity may be recovered if the caregiver takes the time to engage with the person and encourage chewing and swallowing. Specially prepared foods, such as thickened soups, are easier for individuals in the later stages to handle and less likely to cause choking.

Choice D: “Mary endangered Robert by not staying with him to make sure that he did not choke on the piece of chicken” is a good observation.

In the later stages of dementia, protective reflexes, such as the cough and gag reflexes, become weaker or are lost. If Robert accidentally inhaled a piece of the chicken into his windpipe, he could choke, because his cough and gag reflexes may not be strong enough to dislodge the food. In addition to choking, improper swallowing of food or liquid can also cause aspiration pneumonia, which is an infection in the lungs caused by inhaling foreign materials.

Any person can choke on food. However, older people, particularly those with dementia, are at greater risk for choking. The Heimlich maneuver is an accepted method of dislodging food when a person is choking, but in these late stages of dementia, great care should be exercised in applying pressure to the abdomen to avoid injury to bony structures and soft tissue. If someone is choking and coughing, encourage the person to cough and clear the airway. If the person is not able to clear the airway, perform the Heimlich Maneuver using gentle but sharp pressure as prescribed, making sure that the pressure is applied on the upper abdomen, and not the rib cage. If the person is in a wheel chair, place a hand behind the lower back and apply pressure with the other hand.

Click here to learn more about the Heimlich maneuver, click on the provided link.

Choice E: In this case study, all of the choices were good possibilities, therefore choice E, “all of the above,” is the best answer.

Heimlich Maneuver®

The Heimlich Maneuver is the best known and most reliable method for helping a person who is choking. It is an emergency procedure because the person cannot breath or speak and can die.

The Heimlich Maneuver is the best known and most reliable method for helping a person who is choking. It is an emergency procedure because the person cannot breath or speak and can die.

Here are the basic steps for the Heimlich Maneuver.

From behind, wrap your arms around the person’s waist.

Make a fist and place the thumb side of your fist against the person’s upper abdomen, below the ribcage and above the navel.

Grasp your fist with your other hand and press into the person’s upper abdomen with a quick upward thrust. Do not squeeze the ribcage; confine the force of the thrust to your hands.

Repeat until the object is expelled from the mouth.

What you do not want to do is slap the person on the back. This could drive the object deeper into the person’s throat.

Feeding Assistance

A person in the later stages of dementia will need assistance to eat and will take a long of time to complete a meal. During the late to end-stages, individuals can have what is referred to as “feeding apraxia,” which is the inability to feed themselves. With feeding apraxia, the person has forgotten how to chew and swallow and so it becomes necessary to provide considerable assistance for eating.

A person in the later stages of dementia will need assistance to eat and will take a long of time to complete a meal. During the late to end-stages, individuals can have what is referred to as “feeding apraxia,” which is the inability to feed themselves. With feeding apraxia, the person has forgotten how to chew and swallow and so it becomes necessary to provide considerable assistance for eating.

In this section we will discuss some guiding principles and techniques for assisting someone in the later stages of Alzheimer’s to maintain adequate nutrition and hydration. These include recognizing the person’s autonomy, simplifying the task, cueing, positioning the person, assisting with chewing and swallowing, methods of food preparation, and the use of assistive devices.

Feeding Principles

If it is necessary to provide full assistance for the individual, here are some basic principles to follow.

Prepare yourself physically and mentally to share an important and sometimes challenging activity with another person.

Prepare yourself physically and mentally to share an important and sometimes challenging activity with another person.

Sit down and engage with the person, making it a social experience, and devote your time exclusively to the person you are assisting.

Tell the person what is on the plate and what is on the spoon. Give time between spoonfuls, and offer a beverage regularly.

Remember, they are not a “feeder.” They are individuals who need assistance with eating.

Guidelines for Total Assistance with Eating

Here are some general guidelines when a person needs total assistance with eating.

Come to the table with everything you need (food, utensils, condiments, napkins, equipment, and a damp towel).

If the person has a dominant side or prefers to use one side, then sit on that side.

Position yourself at a 90 degree angle to the person.

Tell the person what is on the plate.

Ask if she or he wants a particular food from the plate.

Place a small portion on a spoon and tell the person what you are serving.

Raise the spoon so that it can be seen, and wait for the person to open the mouth.

Give time between bites to chew and swallow the food. Do not hover the next spoonful of food in front of her or his face while waiting.

Offer drinks regularly to wash down food and to hydrate.

If able, encourage or help the person to wipe the lips with a damp towel or soft napkin when needed.

Do not mix foods unless you know that the person prefers the dish that way.

Do not place too much food on the spoon.

Do not scrape excess food from person’s lips or inside of the mouth with the spoon. If a lot of food gets on the mouth, there was probably too much on the spoon.

Do not use a bib. If a bib is necessary, do not wipe the person’s mouth with the bib.

Do not ignore or exclude the person from conversations.

If you have to step away from the meal or are distracted, excuse yourself to the person.

In general, use proper manners and show respect as you would to anyone else.

Principles for Caregiver Assistance with Eating

Although individuals in the later stages of Alzheimer’s will need considerable assistance with eating, it is important to promote independence and the use of remaining capacities. Caregivers should allow as much “self feeding” as the persons can manage. If they can pick up a cooked carrot slice to put in their mouth, the effort should be applauded.

Although individuals in the later stages of Alzheimer’s will need considerable assistance with eating, it is important to promote independence and the use of remaining capacities. Caregivers should allow as much “self feeding” as the persons can manage. If they can pick up a cooked carrot slice to put in their mouth, the effort should be applauded.

Though it is often seen as a task to be completed before moving on to another task, feeding someone is an intimate and bonding interaction that can have a positive effect on the caregiver as well as the care recipient. Caregivers should always show love and respect to the person with dementia regardless of the stage of illness.

Strategies for Assisting with Eating

Simplify the Task

In the later stages of Alzheimer’s, it is important to make everything as simple as possible. It begins with the table setting, which should be simple but attractive and include only the utensils needed. A cup or glass that is easy to hold should be filled only part-way with a liquid.

In the later stages of Alzheimer’s, it is important to make everything as simple as possible. It begins with the table setting, which should be simple but attractive and include only the utensils needed. A cup or glass that is easy to hold should be filled only part-way with a liquid.

Only one food item should be presented at a time on the plate or bowl. Food should be prepared so that it is easily eaten with the same utensil throughout the meal without having to shift from fork to spoon, for example.

Equipment

As the illness progresses and physical abilities decline, the equipment for eating and drinking will need to be modified. For cold beverages, it is helpful to provide a lightweight, plastic glass that can be picked up with arthritic fingers. For warm drinks, a cup with a large handle is easiest to manage. Soup can be served in mugs with handles instead of bowls.

As the illness progresses and physical abilities decline, the equipment for eating and drinking will need to be modified. For cold beverages, it is helpful to provide a lightweight, plastic glass that can be picked up with arthritic fingers. For warm drinks, a cup with a large handle is easiest to manage. Soup can be served in mugs with handles instead of bowls.

When individuals can no longer handle a fork and knife, a spoon with a padded handle can be used.

Communication Strategies

In the later stages of dementia, language skills decline significantly, so people rely more on reading non-verbal clues, including the attitude and demeanor of the caregiver.

In the later stages of dementia, language skills decline significantly, so people rely more on reading non-verbal clues, including the attitude and demeanor of the caregiver.

Therefore caregivers should engage their persons, make eye contact, and sit beside them whether at a table or beside their bed. They should present a calm, pleasant demeanor, an easy smile, and say the person’s name in a pleasant, “upbeat” tone. Caregivers should use simple language, repeat and rephrase as needed, and say the important words last. For example, “Robert, it’s time for your breakfast. (pause) Let me help you with your breakfast.”

Assistance Techniques

Mirroring and Cueing

Now let’s discuss some general techniques for assisting someone in activities.

The principle of graded helping underlies all of these techniques. Graded helping is a way to support independence by helping individuals with only the tasks that they are unable to do by themselves.

One way of “graded helping” is called “mirroring” or showing the person by example. To do this, caregivers can sit down at the table with their care receivers, greet them with a smile and begin eating from their own plate while maintaining eye contact. By watching their caregivers, individuals often mirror or imitate the same behavior.

“Cueing” means giving someone a signal to start or resume an activity. It can be done non-verbally with gestures and a smile.

Cueing can be quite subtle, such as a plate of food, the dining room setting, food fragrances, and sounds.

Cueing can be quite subtle, such as a plate of food, the dining room setting, food fragrances, and sounds.

Stronger cues would include handing the person a spoon and tapping her or his hand. Tapping on the person’s hand and pointing to the food, however, must be done gently and tactfully, as those actions could come across as aggressive.

Verbal cues are useful for encouraging someone to chew and swallow food.

Here is an example of cueing.

Guiding

“Guiding” means to place your hand over a someone else’s hand to guide them through a task, such as scooping up a spoonful of food. You should let go as soon as you feel the person taking over the movement independently. Always be sensitive to the person’s comfort with your touch. Be gentle and respectful.

“Guiding” means to place your hand over a someone else’s hand to guide them through a task, such as scooping up a spoonful of food. You should let go as soon as you feel the person taking over the movement independently. Always be sensitive to the person’s comfort with your touch. Be gentle and respectful.

And be prepared to back away if the person becomes agitated.

Sequencing

“Sequencing” means to maintain a logical, consistent pattern, which can help someone with dementia remember a sequence of tasks. In the case of eating, a logical, consistent routine should be followed for preparing, serving and assisting with a meal. An example of a routine would be to start with assisting the person to use the toilet, wash hands, move to the dining area, sit down, and place a napkin on the lap. First, serve a beverage, then a plate or bowl with one food item. Serve the remainder of the meal in steps – one part of the meal at a time. This will reduce confusion. During the routine, it is important to monitor for fatigue.

“Sequencing” means to maintain a logical, consistent pattern, which can help someone with dementia remember a sequence of tasks. In the case of eating, a logical, consistent routine should be followed for preparing, serving and assisting with a meal. An example of a routine would be to start with assisting the person to use the toilet, wash hands, move to the dining area, sit down, and place a napkin on the lap. First, serve a beverage, then a plate or bowl with one food item. Serve the remainder of the meal in steps – one part of the meal at a time. This will reduce confusion. During the routine, it is important to monitor for fatigue.

Positioning

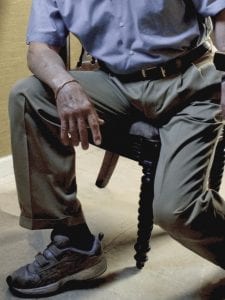

“Positioning” refers to helping the person into an optimal body position for the activity. In the case of eating, this involves chewing, swallowing and digesting food. Mealtime is always better if the person is seated in a chair rather than a wheelchair. The person in this first photo looks very uncomfortable and not in a very good position to take in or digest food.  Ideally, people should sit in chairs with their hips at a 90% angle. Sitting in a chair with armrests can help with positioning. They should sit back in the chair so that their thighs are supported to within 2 inches of the backs of the knees with their feet on the floor. There should be an even distribution of weight, so that the body is not leaning to one side. Their body needs to be about 4 inches from the table, close enough to reach the food without straining.

Ideally, people should sit in chairs with their hips at a 90% angle. Sitting in a chair with armrests can help with positioning. They should sit back in the chair so that their thighs are supported to within 2 inches of the backs of the knees with their feet on the floor. There should be an even distribution of weight, so that the body is not leaning to one side. Their body needs to be about 4 inches from the table, close enough to reach the food without straining.

If a wheel chair is necessary, it should be a firm seat, not a sling seat. Armrests should support their elbows without causing their shoulders to hike up. Armrest should also be set at the correct width to avoid arms slipping down. A lap tray may be used, but even in a wheel chair, it is best to sit at a table.

Assisting a person to eat in bed should be used only when no other alternative is possible.

The person should be as upright as possible. This can be achieved with a “hospital bed” or by propping the person up with sturdy pillows. Support should also be placed under the knees so that they are slightly bent. A slight forward tilt of the head will make chewing and swallowing easier as well as help prevent choking. A pillow or your hand behind her or his head may be used to give support during feeding. The caregiver should sit on the person’s dominant or preferred side. A smile and an occasional conversational comment from the caregiver will contribute to a pleasant atmosphere and aid in the eating process.

Chewing and Swallowing Assistance

There are several factors that can impede a person’s ability to take in food. These include: holding food in the mouth, biting the spoon, spitting food out, and choking when trying to swallow. These are manifestations of “chewing and swallowing apraxias,” the loss of the ability to chew and swallow food.

There are several factors that can impede a person’s ability to take in food. These include: holding food in the mouth, biting the spoon, spitting food out, and choking when trying to swallow. These are manifestations of “chewing and swallowing apraxias,” the loss of the ability to chew and swallow food.

Apraxia refers to a person’s loss of ability to carry out automatic behaviors such as walking, brushing teeth, or driving a car.

Chewing is an automatic behavior learned in the first years of life. The person may want to chew but the brain pathways between wanting to act and initiating the action are lost. In this situation, caregivers may be able to help by placing their hand under the jaw and gently moving it up and down. The person’s muscles may then take over the action.

Pocketing and Choking

Holding food in the mouth is sometimes called “pocketing”. The person pushes food to one side of the mouth and keeps it there as she or he talks or takes in more food. Caregivers need to be alert for a bulge in the person’s cheek, as it could result in choking.

Holding food in the mouth is sometimes called “pocketing”. The person pushes food to one side of the mouth and keeps it there as she or he talks or takes in more food. Caregivers need to be alert for a bulge in the person’s cheek, as it could result in choking.

If you notice that someone “pockets” food, make sure that you offer only small amounts of food on the spoon. Be sure the food is cut into small pieces and is easy to chew.

You could also offer fluids after each bite after the person has had time to chew the food.

At all times when assisting someone who has chewing and swallowing apraxias, monitor closely for the possibility of choking.

Swallowing

When someone is in the late stages of dementia, swallowing apraxia can be severe and made worse by muscle weakness. The person may be unable to swallow and in danger of inhaling food into the lungs. Caregivers needs to watch for signs that someone is having difficulty swallowing.

People who have trouble swallowing may have any of the following signs: they may clear the throat frequently, have a “wet” or “gurgle” sound to their voice, or delay swallowing food that has been chewed. They may swallow several times with one bite of food yet still have food remaining in their mouth. Coughing or fatigue during or after a meal, and significant weight loss over time are other signs of swallowing difficulties.

If a person has difficulty swallowing, a healthcare professional should be consulted to determine the cause and develop a treatment plan. Pureed food and thickened liquids can help overcome some swallowing difficulties.

Positioning the head by tucking the chin to relax the food canal can also help with swallowing. This will also help prevent food from going down into the windpipe and into the lungs.

Spitting Food

Spitting food out is another result of chewing or swallowing apraxia. It is a way for the person to get rid of the food when they cannot chew or swallow. The methods previously discussed, such as verbal cueing and positioning of the head and chin to promote swallowing may be helpful.

Bruxism

Biting the spoon is another sign of feeding apraxia. Sometimes called “bruxism”, individuals may bite the spoon and not let go. They may also grind their teeth without realizing it.

Biting the spoon is another sign of feeding apraxia. Sometimes called “bruxism”, individuals may bite the spoon and not let go. They may also grind their teeth without realizing it.

If the person is prone to biting like this, spoons with a soft coating can be used to prevent damage to teeth and gums. Make sure that the coating firmly adheres to the spoon and will not come off in their mouth. A common plastic spoon should not be used, as it could splinter and injure the person’s mouth.

When placing the spoon in the person’s mouth, use a slight downward pressure to the lower lip as a cue not to bite on it. Then, remove the spoon from the mouth as soon as the food has left the spoon to prevent sucking on it. Sucking is a reflex used in early childhood that often returns in the late stages of dementia.

Assistive Devices

Assistive devices can help people who are having difficulty feeding themselves. These include the rocker knife, a plate guard, and a universal cuff for holding a spoon or other implement. The rocker knife makes it easer to cut food up. The plate guard helps in scooping food up, and the universal cuff secures the utensil to the individual’s hand. Caregivers can even wrap and secure a small washcloth around a spoon handle to make it easier for the person to hold. Assistive devices can be quite beneficial, taking care to preserve the independence and dignity of the individual.

Assistive devices can help people who are having difficulty feeding themselves. These include the rocker knife, a plate guard, and a universal cuff for holding a spoon or other implement. The rocker knife makes it easer to cut food up. The plate guard helps in scooping food up, and the universal cuff secures the utensil to the individual’s hand. Caregivers can even wrap and secure a small washcloth around a spoon handle to make it easier for the person to hold. Assistive devices can be quite beneficial, taking care to preserve the independence and dignity of the individual.

Summary

In summary, people with dementia should eat a well-balanced diet consisting of nutrient-dense foods such as fruits, vegetables, dairy, lean meat, fish, poultry, and whole grains. Brain healthy foods are rich in antioxidants (such as polyphenols, vitamins C and E), folate, vitamins B6 and B12, and unsaturated fatty acids, such as omega-3 fatty acid. Supplements of vitamins and minerals can also help delay brain aging.

Drinking enough liquids is critical for good health, especially among elders with dementia, who are very vulnerable to dehydration. Liquids should be offered throughout a meal and at least every 2 hours during the day.

Weight loss, feeding apraxia, and choking become serious issues during the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. It is important to engage individuals, simplify tasks, and assist using various techniques such as mirroring, cueing, and hands-on guiding.

Proper positioning of the person whether in a chair, a wheel chair or a bed, is important for eating and digesting food. Assistive devices can help individuals remain more independent as well as.

While assisting someone with feeding, caregivers should follow the guiding principles of promoting independence, love, and respect.

← Previous Lesson (Managing Incontinence)

→ Next Lesson (Memory Impairment: Risk Factors)

. . .

Written by: Catherine M. Harris, PhD, RNCS (University of New Mexico College of Nursing)

Edited by: Mindy J. Kim-Miller, MD, PhD (University of Chicago School of Medicine)

References:

- Biernacki C, Barratt J. Improving the nutritional status of people with dementia. Br J Nurs 2001 Sep 27-Oct 10;10(17):1104-1114.

- Morris M. C. Diet and Alzheimer’s Disease: What the evidence shows. MedGenMed. 2004;6(1).

- Poehlman E T., Dvorak R. V. Energy expenditure, energy intake, and weight loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71(suppl):650S-655S.

- Roberts S, & Durnbaugh T, (2002). Enhancing nutrition and eating skills in long-term care. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly 3(4): 316-328.

- Zigola, J. & Bordillon, G. (2001). Bon Appetit!: The joy of dining in long-term care. Baltimore. Health Professions Press. Chapter 8, pp. 138-140.

- Ames BN. 2006. Low micronutrient intake may accelerate the degenerative diseases of aging through allocation of scarce micronutrients by triage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:17589-94.

- Barberger-Gateau P et al. 2007. Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: the Three-City cohort study. Neurology. 69:1921-30.

- Chandra RK. 2001. Effect of vitamin and trace-element supplementation on cognitive function in elderly subjects. Nutrition. 17: 709–12.

- Dirks AJ, Leeuwenburgh C. 2006. Caloric restriction in humans: potential pitfalls and health concerns. Mech Ageing Dev. 127:1-7.

- Engelhart MJ et al. 2002. Dietary intake of AOXs and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 287: 3223–9.

- Morris MC et al. 2002. Vitamin E and cognitive decline in older persons. Arch Neurol. 59: 1125–32.

- Everitt AV et al. 2006. Dietary approaches that delay age-related diseases. Clin Interv Aging. 1:11-31.

- Fontan-Lozano A et al. 2007. Caloric restriction increases learning consolidation and facilitates synaptic plasticity through mechanisms dependent on NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor. J Neurosci. 27:10185-95.

- Head E. 2007. Combining an antioxidant-fortified diet with behavioral enrichment leads to cognitive improvement and reduced brain pathology in aging canines: strategies for healthy aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1114:398-406.

- Ingram DK, Young J, Mattison JA. 2007. Calorie restriction in nonhuman primates: assessing effects on brain and behavioral aging.Neuroscience. 145:1359-64.

- Joseph JA, Shukitt-Hale B, Casadesus G. 2005. Reversing the deleterious effects of aging on neuronal communication and behavior:beneficial properties of fruit polyphenolic compounds. Am J Clin Nutr. 81(1 Suppl):313S-16S.

- Joseph JA, Shukitt-Hale B, Lau FC. 2007. Fruit polyphenols and their effects on neuronal signaling and behavior in senescence. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1100:470-85.

- Jou MJ et al. 2007. Melatonin protects against common deletion of mitochondrial DNA-augmented mitochondrial oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Pineal Res. 43:389-403.

- Lau FC, Shukitt-Hale B, Joseph JA. 2007. Nutritional intervention in brain aging: reducing the effects of inflammation and oxidative stress.Subcell Biochem. 42:299-318.

- Levenson CV, Rich NJ. 2007. Eat less, live longer? New insights into the role of caloric restriction in the brain. Nutr Rev. 65:412-5.

- Luchsinger JA, Noble JM, Scarmeas N. 2007. Diet and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 7:366-72.

- Morris MC et al. 2005. Relation of the tocopherol forms to incident Alzheimer disease and to cognitive change. Am J Clin Nutr. 81:508-14.

- Ringman et al. 2005. A potential role of the curry spice curcumin in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2:131-6.

- Scalbert A, Johnson IT, Saltmarsh M. 2005. Polyphenols: antioxidants and beyond. Am J Clin Nutr. 81(1 Suppl):215S-7S.

- Schaffer S et al. 2007. Hydroxytyrosol-rich olive mill wastewater extract protects brain cells in vitro and ex vivo. J Agric Food Chem. 55:5043-Seniors. Food pyramid remodeled for seniors. Accessed on 11/27/07 at http://www.fitnessandfreebies.com/seniors/fgp4seniors.html.

- Shanley DP, Kirkwood TB. 2006. Caloric restriction does not enhance longevity in all species and is unlikely to do so in humans.Biogerontology. 7:165-8.

- Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. 1994. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91:10771-8.

- Shukitt-Hale B et al. 2007. Beneficial effects of fruit extracts on neuronal function and behavior in a rodent model of accelerated aging.Neurobiol Aging. 28:1187-94.

- Tufts food guide pyramid for older adults. Accessed on 11/27/07 at http://nutrition.tufts.edu/docs/pyramid.pdf.

- Tully MW, Matrakas KL, Muir J, Musallam K. (1997). The eating behavior scale: a simple method of assessing functional ability in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal Gerontological Nursing 23:9–15.

- Wellman NS. 2007. Prevention, prevention, prevention: nutrition for successful aging. J Am Diet Assoc. 107:741-3.

- Willcox DC, Willcox BJ. 2006. Caloric restriction and human longevity: what can we learn from the Okinawans? Biogerontology. 7:173-7.

- Wu YH, Swaab DF. 2005. The human pineal gland and elatonin in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Pineal Res. 38:145-52.Young GS, Conquer LA, Thomas R. 2005. Effect of randomized supplementation with high dose olive, flax, or fish oil on serum phospholipid fiatty acid levels in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Reprod Nutr Dev. 45:549-58.

- Watts V; Turnpenny B; Brown A (2007). Feeding problems in dementia. Geriatric Medicine, 37(8): 15-6, 18-9.