Welcome to the educational program Late Stages: Behavior and Sleep. This program will discuss common behavior and sleep issues that develop in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease and present some principles and strategies for addressing these behavior and sleep problems.

. . .

You may view the topics in order as presented, or click on any topic listed in the main menu to be taken to that section.

We hope that you enjoy this program and find it useful in helping both yourself and those you care for. There are no easy answers when it comes to the care of another, as every situation and person is different. In addition, every caregiver comes with different experiences, skills, and attitudes about caregiving. Our hope is to offer you useful information and guidelines for caring for someone with dementia, but these guidelines will need to be adjusted to suit your own individual needs. Remember that your life experiences, your compassion and your inventiveness will go a long way toward enabling you to provide quality care.

Let’s get started.

Prefer to listen to this lesson? Click the Play button on the playlist below to begin.

Challenging Behaviors in the Early and Middle Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

Wandering, pacing, rummaging, and catastrophic reactions are commonly seen in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. However, these behaviors become muted in the later stages of the illness. This program will emphasize the challenging behaviors that are more common in the late stages of the illness.

Wandering, pacing, rummaging, and catastrophic reactions are commonly seen in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. However, these behaviors become muted in the later stages of the illness. This program will emphasize the challenging behaviors that are more common in the late stages of the illness.

Click here for more information about behavior modification in all stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Challenging Behaviors in the Late Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

More common in late Alzheimer’s are behaviors such as apathy, negativity, and impaired perceptions. Impaired perceptions include hallucinations, illusions, delusions and paranoia. Examples of negativity include refusal to eat, bathe, or dress.

More common in late Alzheimer’s are behaviors such as apathy, negativity, and impaired perceptions. Impaired perceptions include hallucinations, illusions, delusions and paranoia. Examples of negativity include refusal to eat, bathe, or dress.

Apathy is a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and results from loss of important brain cells and pathways. It is often confused with depression and neglected in discussions or teachings because the person with these behaviors may be quiet, withdrawn and not noticed. However, apathy can contribute to immobility, malnourishment, poor dental hygiene and many other debilitating situations.

Hallucinations, illusions, and delusions (such as paranoia) are perceptual distortions caused by the disease, and they need to be understood as they can lead to physical or verbal aggression.

What causes behavior difficulties? There are many factors that can contribute to the behavior changes seen in Alzheimer’s disease. These include brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease, normal changes of aging, untreated medical conditions, stress from environmental stimuli, and the expectations of family or staff in task performance. Though aging and medical problems can play significant roles in behaviors, in this program, we will focus on the specific effects of Alzheimer’s disease that cause behavior changes.

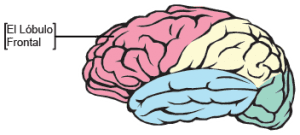

Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia cause damage to the frontal lobe of the brain, which results in loss of impulse control and impaired judgment.

Memory and judgment impairment lead to inappropriate behavior. Additionally, the motivational decline or apathy associated with Alzheimer’s will limit initiative, which can affect physical exercise, nutrition and hydration. Delusions, illusions, and hallucinations are impaired perceptions or misperceptions that can be frightening and can lead to agitation and aggressive behavior. Lastly, the loss of functional abilities can lead to frustration, low self-esteem, changes in self-perception and identify, and behavioral changes.

Changes in the Brain

Two other brain losses worth mentioning are the loss of what is referred to as executive function and decline in the ability to pay attention and concentrate.

Two other brain losses worth mentioning are the loss of what is referred to as executive function and decline in the ability to pay attention and concentrate.

Executive function is located primarily in the frontal lobe and is responsible for goal-directed behavior and abstract thinking. It encompasses planning, following rules, acting appropriately, inhibiting inappropriate actions, impulse control, and selecting relevant sensory information. Executive function is important for decisions and judgments about money, relationships, safety, motivation and social behavior.

Attention and concentration are dependent on a number of brain components that deteriorate in Alzheimer’s. Because these functions decline, persons with dementia are at risk for malnutrition and entering unsafe situations.

Apathy and depression are related but are different. Apathy is a dulled emotional state characterized by indifference, diminished initiative, poor persistence in an activity, lack of interest, and lack of insight. Apathetic people show little or no emotions and seem uninterested in interacting with others. Apathy can actually be a symptom of depression. The major symptoms of depression include a marked lack of interest, loss of motivation, feelings of hopelessness, fatigue, poor concentration, difficulty making decisions, and low self-esteem. With depression, the person will often complain of fatigue and appear sad with a sad facial expression and may worry about concerns such as health and finances. The individual may have disturbances in appetite and sleep. So in general, a depressed person will show some facial expressions, will respond when addressed, and will benefit from anti-depressant medication. In contrast, an apathetic person generally will not show emotion, will not acknowledge other people, and are less likely to respond to anti-depressant medication. The person is more indifferent to problems and surroundings. Though there are differences, it may be difficult to tell apathy apart from depression, because of overlapping symptoms. For example, individuals with either condition can have appetite changes, may sit idly without getting involved in activities, and may neglect personal hygiene including bathing and dressing. Evaluation by a health care professional may be necessary to evaluate the symptoms and the best approach for care. It is important to note that apathy and depression can occur together in the same person.

Apathy and depression are related but are different. Apathy is a dulled emotional state characterized by indifference, diminished initiative, poor persistence in an activity, lack of interest, and lack of insight. Apathetic people show little or no emotions and seem uninterested in interacting with others. Apathy can actually be a symptom of depression. The major symptoms of depression include a marked lack of interest, loss of motivation, feelings of hopelessness, fatigue, poor concentration, difficulty making decisions, and low self-esteem. With depression, the person will often complain of fatigue and appear sad with a sad facial expression and may worry about concerns such as health and finances. The individual may have disturbances in appetite and sleep. So in general, a depressed person will show some facial expressions, will respond when addressed, and will benefit from anti-depressant medication. In contrast, an apathetic person generally will not show emotion, will not acknowledge other people, and are less likely to respond to anti-depressant medication. The person is more indifferent to problems and surroundings. Though there are differences, it may be difficult to tell apathy apart from depression, because of overlapping symptoms. For example, individuals with either condition can have appetite changes, may sit idly without getting involved in activities, and may neglect personal hygiene including bathing and dressing. Evaluation by a health care professional may be necessary to evaluate the symptoms and the best approach for care. It is important to note that apathy and depression can occur together in the same person.

It is not known exactly what part of the brain causes or contributes to apathy. However, scientists believe that the monitoring and decision-making component of the frontal lobe of the brain, the “executive function” is involved. Another area of the brain that could contribute to apathy is damage to the cingulate gyrus, a part of the brain that is related to emotions. In this diagram the cingulate gyrus is identified with a blue star, and the frontal lobe is identifies with a red star.

Let’s discuss a case study about Robert, who is in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. He is wheel-chair bound and living in an Alzheimer care facility. He has lately shown some resistance when taken to the dining room for meals. When he is at the table, he plays with his food but eats very little. He doesn’t acknowledge others at the table. He urinates when taken to the bathroom but doesn’t ask to be taken when he needs to go, so he often urinates in bed.

Let’s discuss a case study about Robert, who is in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. He is wheel-chair bound and living in an Alzheimer care facility. He has lately shown some resistance when taken to the dining room for meals. When he is at the table, he plays with his food but eats very little. He doesn’t acknowledge others at the table. He urinates when taken to the bathroom but doesn’t ask to be taken when he needs to go, so he often urinates in bed.

He appears to be disinterested in the people around him and shows little or no emotion on his face. If not directed to do so, he doesn’t eat, bathe, brush his teeth, or talk to anyone.

The apathy we observe in Robert means that he is indifferent to his surroundings and events. He makes no demands on family or staff, but he has decreasing ability to function in many areas.

- A. Encourage exercise.

- B. Engage in communication.

- C. Start him on medication.

- D. All of the above.

Case Study 1 Answers:

Choice A: “Encourage exercise” is an excellent choice.

Physical exercise increases respiration which increases the oxygen content ofthe blood. And increased circulation carries more blood to the brain, making more oxygen and nutrients available, and taking away more waste products. For it’s size, the brain needs more oxygen and nutrients than any other part of the body.

In the late stages of Alzheimer’s, Robert could benefit from chair exercises such as the ball toss.Including music during exercise can liven the activity and be a good motivating factor.As conditioning improves, exercises can be increased gradually over time as tolerated.

Choice B: “Engage in communication” is another good choice.

To engage means to spend quality time with someone while focusing your attention on that person. In Robert’s case, a caregiver could sit down beside Robert at meal time, say his name and make eye contact. It will take more effort to engage him, because the apathy is biological, not psychological. He is not willfully ignoring people. He just does not have the awareness of his social surroundings.

Robert will benefit greatly from the caregiver’s undivided attention and message of interest. It will take more persistence, and communication will need to be simple. Speak clearly using simple terms, gestures and facial expression to convey the meaning. Try to say the important words last in each sentence to increase the likelihood that it will be remembered.

Here is an example:

Sally: “Robert, it’s time for your bath. I will help you with your bath. Let’s go to the tub room.”

When even a faint response is noted, it can be reinforced with more attention.

Persons who are experiencing apathy will need a great deal of direction. Their levels of awareness and motivation are so low that they will not act on their own.

It may be necessary to use gentle but firm direction in order for someone with apathy to accomplish daily activities such as bathing, dressing, tooth brushing, even eating. If a person is truly apathetic, there is no motivation to do these things.

Choice C: “Start him on medication” is another good possibility.

Various classes of medications can help treat the symptoms of apathy.

Some individuals with apathy may benefit from an antidepressant medication, because depression and apathy can occur together. Some people with apathy benefit from medications that are typically used for psychiatric disorders. Yet another medication, such as a dopamine stimulant used in Parkinson’s disease, could be helpful. In any case, a health care professional should be consulted to carefully evaluate his condition for the class of medication that would be most helpful.

Choice D: Because all of these choices are good options, choice D, “all of the above,” is the best answer in this example.

Robert will need close personal attention from an engaged caregiver to be sure that he has adequate nutrition and that his daily needs are provided for. He will need exercise, direction, and simple, direct communication.

Negativity

Delusions, paranoia and hallucinations can produce a negative mind set in the person experiencing them, particularly in those with dementia, whose ability to process information is very limited. Because they are suspicious and frightened of people and things in their surroundings, they are prone to negative responses to efforts to provide care for them. They are wary of cooperating with others. Caregivers need to be calm and reassuring and use very clear, simple communication to counteract negativity.

Delusions, paranoia and hallucinations can produce a negative mind set in the person experiencing them, particularly in those with dementia, whose ability to process information is very limited. Because they are suspicious and frightened of people and things in their surroundings, they are prone to negative responses to efforts to provide care for them. They are wary of cooperating with others. Caregivers need to be calm and reassuring and use very clear, simple communication to counteract negativity.

Now, let’s discuss hallucinations, illusions, and delusions, which can be seen in dementia of various kinds. A hallucination is the perception of something that is not there. A hallucination can involve any of the senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, or touch). Seeing something that is not there is called a visual hallucination, and hearing something or someone that is not there is an auditory hallucination. These two types of hallucinations can be experienced together or separately. For example, a person may see and hear a deceased family member.

An illusion is somewhat different from a hallucination. An illusion is the misperception or misinterpretation of an object or a person. For example, someone may see a hat rack and misinterpret it as a person. Individuals may see their own image in a mirror or a darkened  window and, not recognizing themselves, believe that another person is in the room. All of these false or mis-perceptions are caused by damage to the parts of the brain that process sensory information, so they seem very real to the person experiencing them.

window and, not recognizing themselves, believe that another person is in the room. All of these false or mis-perceptions are caused by damage to the parts of the brain that process sensory information, so they seem very real to the person experiencing them.

A delusion is a false idea or belief that is strongly held. For example, Robert may wrongly believe that his wife, Mary is having an affair with the male caregiver who comes to assist with his bathing and dressing. Robert may believe that the paid caregiver is stealing his money or trying to take his place in the household. In Alzheimer’s disease, damage to the brain cells and pathways that help make sense of the world result in fear and confusion, which in turn can lead to suspiciousness and paranoia, particularly at night when familiar clues in the surroundings are shadowed. Functional losses can also lower a person’s sense of mastery and self worth, leading to suspicion and fear of people.

Delusions can be a sign of underlying physical illness or depression. At the same time, it is always possible that the person’s delusion has a basis in reality.

Delusions can be a sign of underlying physical illness or depression. At the same time, it is always possible that the person’s delusion has a basis in reality.

Continuing the previous example, if Robert believes that his money was stolen and accuses the paid caregiver, then Mary should investigate and ask the caregiver about the money. In this case, the investigation would include looking in odd places for the money. Keep in mind that persons with memory loss are often fearful of losing valuable items and may hide them in unusual places. It would not be beneficial to argue with Robert, but rather to tune into the feelings that he is expressing.

Paranoia describes unwarranted or exaggerated mistrust or suspiciousness of others that causes excessive fear and anxiety. It often involves a sense of persecution and threat towards oneself. Paranoia can reach the point of being a delusion. For example, a woman with dementia may have the fixed belief that her caregiver is trying to poison her in order to take her belongings. The person may refuse to eat because of this or may attack the caregiver. Even though people with dementia have poor memory, they can retain a strong sense of territory and belongings. Caregivers need to be careful in such situations so as not to give any reason to be suspicious.

Another approach to managing delusions and hallucinations is to consult a healthcare professional about medications that may be able to reduce their occurrence.

Here is a scenario with Robert, who has late stage Alzheimer’s disease. Let’s see how the caregiver responds to Robert.

In that example, the caregiver responded to Robert’s hallucination and paranoia by being argumentative. She was focused more on dismissing the false perceptions and beliefs and moving on with her work. She is not focused on Robert and his well-being. Robert is frightened and that should be the caregiver’s primary concern.

What would be a better way for a caregiver to respond to Robert’s fear?

- A. Investigate the surroundings.

- B. Check for fever or other signs of illness.

- C. Look for environmental causes.

- D. Offer reassurance.

- E. All of the above.

Case Study 2 Answers:

Choice A: “Investigate the surroundings” is a very good response.

The caregiver should investigate what is could be causing this fearful response. Could there be someone in the room? Maybe or maybe not, but as the individual is frightened and has been alone, it is always important to find out the facts. Even if there is no one in the room, investigating will acknowledge and respect the person’s assertions and dignity. Not investigating tells people that their fears are not valid or important. Additionally, the caregiver’s search and assurance that there is no one in the room that could harm him would be very reassuring and help calm him down so that he can go back to sleep.

Diversion

Because of the short attention span and memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease, one useful strategy for managing false perceptions and beliefs is to use diversion or redirecting. For instance, reminiscing about old memories or looking over a family photo album can move a person’s attention away from a frightening experience to a pleasant one. Ask the person to tell you about someone in a photo or about past vacations.

Because of the short attention span and memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease, one useful strategy for managing false perceptions and beliefs is to use diversion or redirecting. For instance, reminiscing about old memories or looking over a family photo album can move a person’s attention away from a frightening experience to a pleasant one. Ask the person to tell you about someone in a photo or about past vacations.

Delusions with paranoia are not easy to address, as they often are so fixed in the person’s mind. Again, it is helpful not to argue, but rather to reassure the person. For example, saying, “Your husband loves you very much,” or “She is very proud of you,” can provide some reassurance. Then try redirecting their attention by asking, “How did you two meet?” or “Will you tell me about your wedding?”

It can be helpful to compliment and “build the person up” before providing a diversion. For example, tell the person that she looks lovely or that he looks handsome. If some individuals like to sing, tell them that you think they sing beautifully and ask them to sing a song with you. Or, if applicable, ask them to tell you about their experiences singing in a group or choir. These strategies will promote self worth and allow people to reminisce about happy times.

Pleasant Hallucinations

It is interesting to note that sometimes hallucinations and delusions can be pleasant. A retired nurse with dementia, for example, may believe that she is passing out medications as the medication nurse for the care facility lets her “assist” by pouring water for the “patients.” Another example might be a resident, who has never been an artist, now believes that she is one, and paints many pictures, which she tries to sell. Another person might have visions of flowers growing in the snow outside of her window.

It is interesting to note that sometimes hallucinations and delusions can be pleasant. A retired nurse with dementia, for example, may believe that she is passing out medications as the medication nurse for the care facility lets her “assist” by pouring water for the “patients.” Another example might be a resident, who has never been an artist, now believes that she is one, and paints many pictures, which she tries to sell. Another person might have visions of flowers growing in the snow outside of her window.

These delusions and hallucinations are not harmful to anyone, and are actually pleasant to those experiencing them. Such phenomenon can be allowed and even used as topics of discussion.

Summary of Challenging Behaviors

Displaying challenging behaviors is a form of communication. It’s very important to determine what the person is trying to communicate with the behaviors.

Hallucinations, illusions, delusions, apathy, and negativity are symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease that can cause challenging behaviors. Many factors contribute to these behavior changes, including normal changes of aging, vision and hearing loss, medical conditions, and environmental factors.

Apathy is characterized by diminished initiative, poor persistence in an activity, indifference, and lack of interest, emotions and insight. Someone suffering from apathy may have appetite changes, may sit idly without getting involved in activities, and may neglect personal hygiene including bathing and dressing. It can contribute to immobility, malnourishment, poor dental hygiene and other debilitating situations. Apathy and depression can occur together in the same person. Strategies for managing apathy include engaging the person, encouraging exercise, and medications.

Hallucinations, illusions, and delusions are perceptual distortions caused by the disease. Hallucinations are false perceptions, illusions are misinterpretations, and delusions are strongly held false beliefs. They can cause fear, frustration, and difficult behaviors. When responding to perceptual distortions, it is important not be argumentative or dismissive. Caregivers should acknowledge the fear and investigate any potential causes. Reassurance, redirection, adaptations to the environment and working with the person to promote mastery and self worth will benefit and help to reduce the negative effects of these symptoms. The key to managing most challenging behaviors is to always treat each person with dignity and respect.

Late-Stage Sleep Issues

Sleep changes can occur fairly early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease, but sleep-wake disruptions will increase as the disease progresses. Nighttime awakenings with wandering, illusions, hallucinations and frightening nightmares can pose problems for caregivers. Some people with dementia may even have a complete reversal of the usual daytime wakefulness/ nighttime sleepiness pattern. By the late stages of dementia, many will spend their time in bed awake at night and a significant portion of their daytime hours napping.

Sleep changes can occur fairly early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease, but sleep-wake disruptions will increase as the disease progresses. Nighttime awakenings with wandering, illusions, hallucinations and frightening nightmares can pose problems for caregivers. Some people with dementia may even have a complete reversal of the usual daytime wakefulness/ nighttime sleepiness pattern. By the late stages of dementia, many will spend their time in bed awake at night and a significant portion of their daytime hours napping.

In the late stages of dementia, they may actually sleep more, but their sleep is almost exclusively light and compensates poorly for the loss of deep, restful sleep.

End-Stage Sleep Issues

In the terminal or end stage of the illness, the level of wakefulness and alertness diminishes to become a near comatose condition. Rousing the individual to take nourishment and medications may become difficult.

In the terminal or end stage of the illness, the level of wakefulness and alertness diminishes to become a near comatose condition. Rousing the individual to take nourishment and medications may become difficult.

Non-Pharmacological Sleep-Wake Cycle Interventions

Treatment of sleep-wake cycle disturbances is important, as better sleep can lead to improved mental and physical function. Effective management of sleep may lead to improved day-to-day functioning including toileting, eating, and personal hygiene.

However in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease, it is a difficult issue. Medications that promote sleep in healthy persons can dampen mental functioning and capacities in someone with dementia. So caregivers should always start with non-pharmacological approaches for managing sleep issues.

These approaches include increasing daytime activity to reduce daytime napping. Examples of activities that promote alertness include sing-alongs, chair exercises, walking or even moving about in a wheel chair.

Exposure to bright light during the day, either with sunlight or a light box, can help normalize the biological clock or circadian rhythm. Older people generally do not see enough daylight. Some elders get as little as 30 minutes of daylight a day. This is not enough to maintain the circadian rhythm. People should get sunlight exposure for several hours if possible, especially in the morning. Even in cooler weather, if people are bundled up and sit in an area protected from wind, the outdoors can provide stimulation and help restore normal circadian rhythm. If going outside is not possible, then let sunlight into the room or light up a room as much as possible during the day. A light box is a great alternative to natural sunlight. Studies have shown that using a light box during the day can help improve sleep patterns and reduce agitation and difficult behaviors.

Exposure to bright light during the day, either with sunlight or a light box, can help normalize the biological clock or circadian rhythm. Older people generally do not see enough daylight. Some elders get as little as 30 minutes of daylight a day. This is not enough to maintain the circadian rhythm. People should get sunlight exposure for several hours if possible, especially in the morning. Even in cooler weather, if people are bundled up and sit in an area protected from wind, the outdoors can provide stimulation and help restore normal circadian rhythm. If going outside is not possible, then let sunlight into the room or light up a room as much as possible during the day. A light box is a great alternative to natural sunlight. Studies have shown that using a light box during the day can help improve sleep patterns and reduce agitation and difficult behaviors.

At night, it is helpful to darken the room as much as safely possible. This will promote the best production of melatonin, the body’s sleep hormone. If the person wanders at night, it is important to leave on enough lights or nightlights to prevent injury. The room should also be quiet and away from noise and traffic that could be disturbing.

Non-Pharmacological Sleep-Wake Cycle Interventions (Continued)

Other aspects of good “sleep hygiene” include keeping a consistent schedule for getting up and for going to bed. Keep regular routines by establishing a relaxing nighttime routine. A nighttime ritual of changing clothes, brushing teeth and using the toilet if capable is beneficial. Make sure that the person is comfortable and warm enough in the bed. Some may want to have a goodnight prayer. Some may want soft music for a while as they begin to doze. Remember, if there is a new caregiver, have the previous caregiver accompany the new one during the first one or two days and nights in order to introduce the new caregiver and help establish a connection.

Limit daytime napping to 20 to 30 minutes and avoid naps in the late afternoon and evening. The bed should be used primarily for sleeping, so, if possible, have the person out of the bed while awake. Try to prevent the person from watching television while trying to fall asleep, as it can keep the body stimulated or cause distress and nightmares.

Limit daytime napping to 20 to 30 minutes and avoid naps in the late afternoon and evening. The bed should be used primarily for sleeping, so, if possible, have the person out of the bed while awake. Try to prevent the person from watching television while trying to fall asleep, as it can keep the body stimulated or cause distress and nightmares.

Try to minimize the person’s pain and fatigue, which are frequent causes of insomnia or poor sleep. Sometimes it is difficult for someone with dementia to tell others about pain or fatigue, so caregivers should learn to read body language and look for signs of pain or discomfort. Signs can include increased agitation, the holding, guarding, or favoring of certain body parts, decreased mobility, wincing, feeling cold or feverish to the touch, or rapid breathing. It is important to treat pain as much as safely possible, especially prior to bedtime. Talk to a healthcare professional about pain management.

Look for and attend to other causes of discomfort, such as a full bladder, constipation and incontinence. You should encourage the person to use the toilet before going to bed.

Lastly, talk to a healthcare professional for more information about other factors that can affect sleep including medical conditions, anxiety, depression, and medications. You can also discuss medications and non-drug therapies that promote sleep.

Non-Pharmacological Sleep-Wake Cycle Interventions (Continued)

It is important to keep in mind that what people eat and drink can affect how well they sleep. Therefore caregivers should control the person’s diet and fluid intake.

It is important to keep in mind that what people eat and drink can affect how well they sleep. Therefore caregivers should control the person’s diet and fluid intake.

Don’t let the person drink too much fluid in the evening. This can lead to frequent trips to the toilet at night.

Restrict the use of alcohol. Alcohol may help a person to fall asleep, but it has a rebound effect, which causes awakening later on.

Avoid caffeinated products in the late afternoon and evening, Remember that caffeine can be found in drinks as well as foods such as chocolate.

Avoid heavy or rich food late in the evening, but try giving the person a light snack before bedtime. A light snack of foods that promote sleep may reduce awakenings caused by nighttime hunger.

Some foods can help promote sleep. Try serving sleep-promoting foods for dinner or an evening snack. Examples of such foods include dairy products, such as cheeses and milk. Soy products such as tofu and soybeans, along with other beans and lentils. Whole grains, rice and oats, along with a variety of nuts and seeds, including peanuts, almonds and sunflower seeds. Proteins such as eggs, fish and poultry. Lastly, certain fruits and vegetables including avocados, peaches, asparagus and bananas might help to promote sleep.

Managing Nighttime Awakening

When people awaken at night, it is best to assume that they are disoriented. This is the time to provide gentle orientation about who you are and where they are, and reassure them that everyone is safe and everything is okay. Then remind them that it is time for sleeping. Sometimes people with dementia forget that they were even sleeping and just the suggestion: “Well, it’s time to get into bed and go back to sleep” might work.

When people awaken at night, it is best to assume that they are disoriented. This is the time to provide gentle orientation about who you are and where they are, and reassure them that everyone is safe and everything is okay. Then remind them that it is time for sleeping. Sometimes people with dementia forget that they were even sleeping and just the suggestion: “Well, it’s time to get into bed and go back to sleep” might work.

If the usual efforts to help them go back to sleep don’t work, sometimes it is best to let them engage in a quiet activity and have a glass of warm milk, and then sit with them for a while in the darkened room until they are ready to fall asleep.

Click here for more information about managing nighttime awakening and other sleep issues.

For more information about managing nighttime awakenings and other sleep issues, click here.

Managing Hallucinations and Illusions

Sometimes people with dementia awaken from sleep and experience hallucinations or illusions. The illusion or hallucination is very real to them, so provide reassurance and diversion. Use reassuring words, a calm voice, and comforting touch if appropriate. Reassure the person that everyone is safe and everything is fine.

Do not argue or try to convince people that the hallucination or illusion is not real. If the false perception is not causing any harm to anyone, do not try to correct it. In fact, use it as a topic of conversation and then move onto another topic.

Rather than arguing about the false perception, show individuals that you respect their feelings by investigating their concern. For example, if they believe that someone is in the room or building, offer to look around to reassure them that no one is there. If they believe that something is missing or has been stolen, offer to help look for the object. If they believe that someone has been hurt, offer to help call that person in the morning to make sure that she or he is safe. Whatever the situation, offer reassurance and comfort.

Rather than arguing about the false perception, show individuals that you respect their feelings by investigating their concern. For example, if they believe that someone is in the room or building, offer to look around to reassure them that no one is there. If they believe that something is missing or has been stolen, offer to help look for the object. If they believe that someone has been hurt, offer to help call that person in the morning to make sure that she or he is safe. Whatever the situation, offer reassurance and comfort.

Then try distracting the person’s attention onto something else, such as listening to music, talking about past travels, reading to the person, looking at photos, counting money, playing a game, or offering a snack. Or consider asking about whatever frightened them. For example, you can ask, “What did you see that frightened you?” Discuss it calmly to relax the person and try to find the meaning or source of the false perception.

Lastly, investigate the possibility that something in the environment caused the hallucination or illusion. Look around and change things in the environment that may be triggering the misperception. Some examples of potential triggers include, distortions from walls, floors, and furniture, noises, whispering or talking when the person cannot see who is speaking, glare, reflections and shadows. For example, if the person believes there is a stranger in the mirror, take the mirror down or cover it up. You can also try changing the room lighting so that there is less glare and shadows and try not to whisper or talk when the person is not facing you.

These strategies can help caregivers reduce and manage hallucinations, illusions, and delusions.

Managing Nightmares

Nightmares can cause people to wake up frightened and confused. If someone with dementia wakes up frightened by a nightmare, listen to what the person is saying and look for clues about what is causing stress. People with dementia may have trouble expressing their thoughts and feelings. Reassure them that they are safe and that their family and friends are safe as well.

Nightmares can cause people to wake up frightened and confused. If someone with dementia wakes up frightened by a nightmare, listen to what the person is saying and look for clues about what is causing stress. People with dementia may have trouble expressing their thoughts and feelings. Reassure them that they are safe and that their family and friends are safe as well.

Try to remove any triggers or sources of stress from the person’s environment. For example, people with dementia may not understand new information or an event and may interpret the situation in a way that causes them fear. Therefore watching news programs, violent or scary movies or TV shows may be a source of fear and confusion. If these things cause nightmares or prevent sleep, try to keep the person away from them, especially before bed.

Summary of Sleep Issues

In summary, late stage sleep issues include changes in sleep-wake patterns, nighttime awakenings, hallucinations, illusions, and nightmares. Practicing good sleep hygiene, such as a consistent evening routine and a supportive environment, can help improve sleep at night. Getting exercise and light therapy can also help normalize sleep patterns. The foods one eats can also affect sleep patterns as some foods can hinder or help promote sleep.

In summary, late stage sleep issues include changes in sleep-wake patterns, nighttime awakenings, hallucinations, illusions, and nightmares. Practicing good sleep hygiene, such as a consistent evening routine and a supportive environment, can help improve sleep at night. Getting exercise and light therapy can also help normalize sleep patterns. The foods one eats can also affect sleep patterns as some foods can hinder or help promote sleep.

If someone awakens from sleep frightened, it is important to offer reassurance and comfort. Investigate for possible causes for their concern, then try to distract them onto more pleasant, relaxing topics. Also try to adjust or remove any environmental factors or sources of stress that may be triggering the frightening hallucinations, illusions, or nightmares.

Click here to learn more about sleep issues.

← Previous Lesson (Late Stages: Personal Care)

→ Next Lesson (Managing Incontinence)

. . .

Written by: Catherine M. Harris, PhD, RNCS (University of New Mexico College of Nursing)

Edited by: Mindy J. Kim-Miller, MD, PhD (University of Chicago School of Medicine)

References:

- Allen RS, Burgio LD, Fisher SE, Hardin JM, & Shuster JL, (2005). Behavioral characteristics of agitated nursing home residents with dementia at the end of life. The Gerontologist 45: 661-666.

- Bayles, K.A., Tomoeda, C.K., Cruz, R.F. & Mahendra, N. (2000). Communication abilities of individuals with late-stage Alzheimer Disease.Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 14 (3), 176-181.

- Bernick L, Nisan C, Higgins M. (2002). Care of the body: maintaining dignity and respect. Perspectives.;26(4):10-4.

- Boyd CO and Vernon GM. (1998). Primary care of the older adult with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease. The Nurse Practitioner. 23 4:63–83.

- Bliwise DL. (1993). Sleep in normal aging and dementia. Sleep, 16, 40-81.

- Broton, M., & Koger, S.M. (2000). The impact of music therapy on language functioning in dementia. Journal of Music Therapy Association,37 (3), 183-195.

- Calkins M; Szmerekovsky JG; Biddle S. (2007). Effect of increased time spent outdoors on individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 21(3-4): 211-28.

- Chalmers, J. (2000). Behavior management and communication strategies for dental professionals when caring for patients with dementia.Special Care in Dentistry, 20 (4), 147-154.

- DeLegge MH. (2008). Enteral feeding. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology24(2): 184-9.

- Eisdorfer C, Cohen D, Paveza GJ, et al. (1992). An empirical evaluation of the global deterioration scale for staging Alzheimer’s disease.American Journal of Psychiatry 149(2):190–194.

- Ekman, S., Norberg, A., Viitanen, M. & Winblad, B. (1991). Care of demented patients with severe communication problems. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 5 (3), 163-170.

- Epps, C.D. (2001). Recognizing pain in the institutionalized elder with dementia. Geriatric Nursing, 22 (2), 71-77.

- Gleeson, M. & Timmins, F. (2004). Touch: a fundamental aspect of communication with older people experiencing dementia. Nursing Older People 16 (2), 18-21.

- Gotell, E., Brown, S., & Ekman, S. (2002). Caregiver singing and background music in dementia care. Western Journal of Nursing Research,24 (2), 195-216.

- Hoffman, SB & Kaplan M. (1996). Special care programs for people with dementia. Health Professions Press.Baltimore.

- Kim, W.J., & Buschmann, M.T. (1999). The effect of expressive physical touch on patients with dementia. International Journal Nursing Studies, 36 (1999), 235-243.

- Martin JL; Ancoli-Israel S. (2008). Sleep disturbances in long-term care. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 24(1): 39-50.

- O’Donovan, S. (1996). A validation approach to severely demented clients. Nursing Standard. 11 (13-15), 48-52.

- Paniagua MA; Paniagua EW. (2008). The demented elder with insomnia. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 24(1): 69-81.

- Prigerson, HG (2003). Costs to Society of Family Caregiving for Patients with End-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2003 Nov 13;349(20):1891-2.

- Rao V; Spiro J; Samus QM; Steele C; Baker A; Brandt J; Mayer L; Lyketsos CG; Rosenblatt A. (2008). Insomnia and daytime sleepiness in people with dementia residing in assisted living: findings from the Maryland Assisted Living Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 23(2): 199-206.

- Vitiello MV & Prinz PN. (1989). Alzheimer’s disease: Sleep and sleep/wake patterns. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 5 (2), 289-298.

- Vitiello MV, Bliwise DL & Prinz PN. (1992). Sleep in Alzheimer’s disease and the sundown syndrome. Neurology, 42(6, suppl.), 83-94.

- Volicer L. (2005). End-of-life Care for People with Dementia in Residential Care Settings. Alzheiemer’s Association. Retrieved from http://www.alz.org/national/documents/endoflifelitreview.pdf.

- Watts V; Turnpenny B; Brown A (2007). Feeding problems in dementia. Geriatric Medicine, 37(8): 15-6, 18-9.