Welcome to the educational program Assisting with Activities of Daily Living: Dressing. This program will present principles for assisting people with Alzheimer’s disease to perform activities of daily living, also called ADLs or self-care activities, with a focus on the activity of dressing. This program will help you understand the factors that can make dressing a challenging activity for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers, and provide tips for assisting with dressing.

. . .

This is Lesson 4 of The Alzheimer’s Caregiver. You may view the topics in order as presented, or click on any topic listed in the main menu to be taken to that section. We hope that you enjoy this program and find it useful in helping both yourself and those you care for.

There are no easy answers when it comes to the care of another, as every situation and person is different. In addition, every caregiver comes with different experiences, skills, and attitudes about caregiving. Our hope is to offer you useful information and guidelines for caring for someone with dementia, but these guidelines will need to be adjusted to suit your own individual needs.

Remember that your life experiences, your compassion, and your inventiveness will go a long way toward enabling you to provide quality care.

Let’s get started.

Prefer to listen to this lesson? Click the Play button below.

Aging Factors

Alzheimer’s disease typically affects people in their older years, so the changes associated with aging, as well as dementia, must be taken into consideration. Aging factors that affect bathing include the person’s skin, which becomes thinner and more fragile, making it easier to bruise or injure. The body’s temperature regulating system declines with aging, so older people are more sensitive to temperature, particularly to cold. They may feel chilled even when others feel warm. Due to declining vision and hearing, older people may not be able to hear instructions well or see things clearly, such as the hot and cold labels on water taps. With aging, joints can become stiff and painful, which can limit motion and cause unsteadiness. This is especially important because falls become a greater risk due to reduced mobility and balancing ability.

Dementia Factors

In addition to aging, changes associated with dementia also contribute to loss of functionality. Dementia causes memory loss, or amnesia. This loss of memory initially involves predominantly short-term memory, such as where they put their slippers or when they last had a bath. Over time, the memory loss includes more and more distant memories. Automatic skills, such as bathing and brushing teeth, are also gradually forgotten due to damaged brain cells. The loss of automatic skills or inability to use common objects is called apraxia.

Recognition, or the ability to recognize images, also declines as Alzheimer’s progresses. For example, the person may not recognize a bottle of shampoo or washcloth. This inability to recognize objects is called agnosia.

Alzheimer’s disease also affects the language centers of the brain. So the person will have increasing difficulty understanding and creating speech. This is called dysphagia or aphasia.

Attention and concentration decline as well. As Alzheimer’s progresses, the ability to pay attention and concentrate on a task gradually decreases.

Stress threshold recognition declines, meaning that people with Alzheimer’s often do not know when or how much they are stressed. They also have a lower threshold for stress, so they feel stress more easily. Their ability to avoid stress also decreases, and they cannot anticipate when stress may increase.

Impulse control declines.The ability to control one’s impulses is called the executive function. Alzheimer’s causes damage to the front part of the brain, which controls executive function. Poor impulse control can lead to yelling, fighting, hitting, pinching, or throwing things.

Additionally, organizational ability declines. Damage to the front part of the brain also results in loss of organizational ability. Self-care activities require organizational ability: that is, knowing what to do, when to do it, and how to put prepare the necessary items.

Lastly, people with dementia can have difficulty adjusting to new surroundings, which may cause confusion, fear, and a negative reaction to performing activities of daily living. When planning and assisting with ADLs, you should consider whether the person is in an unfamiliar environment, such as a long-term care facility.

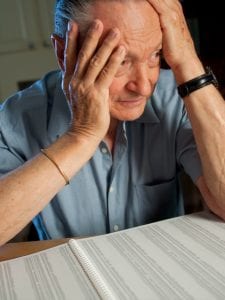

Case Study 1

Let’s begin with a case study about Mary and her husband, Robert, who has Alzheimer’s disease. What might be happening in this situation?- A. Robert put on the dirty shirt and pajama bottoms, because they were closest to him.

- B. Mary was frustrated and focused on the task rather than on Robert.

- C. Robert couldn’t figure out how to get dressed.

- D. All of the above.

Case Study 1 Answers:

Choice A: “Robert put on the dirty shirt and pajama bottoms because they were closest to him” is a good answer.

When people have limited reasoning abilities, their tendency is to simply react mechanically to what is in the environment. So if Robert wants to get dressed, he will probably put on the clothes that are at hand or the most easily accessible. In this case, the dirty clothes were the closest to Robert so he put them on.

Choice B: “Mary was frustrated and focused on the task rather than on Robert” is also a good answer.

Mary had become frustrated while helping Robert with the shower, and then felt rushed to get lunch prepared. When she saw Robert and the wrong clothes after his bath, she became more frustrated, because she now had to take time to select new clothes for him and help him change into them. This would put Mary even further behind schedule, so she scolded Robert because of the situation rather than focusing on Robert and his needs. When caregivers feel overly stressed, they sometimes say things they don’t mean to say or make mistakes they wouldn’t otherwise make. Stress can even lead to care recipient abuse. It can also make people more vulnerable to illness, depression, and other serious health problems. Therefore, caregivers need to monitor their stress levels and take steps to reduce unhealthy levels of stress. This includes asking for help when needed, having outside social contacts, and attending to their own health with medical care, exercise, and a healthy diet.

Choice C: “Robert couldn’t figure out how to get dressed” is a great answer.

As Robert’s Alzheimer’s disease progressed, he lost the ability to plan and organize his personal care activities. He had dressing apraxia, which means that he forgot how to dress and couldn’t match his intention to get dressed with the actions required to do it. Robert’s ability to master his personal care and environment has declined due to a disease. This has resulted in a sense of frustration and loss of self-esteem. Although many of his cognitive and functional abilities have been lost, he can still sense how others feel about him. Because his ability to understand words has declined, he relies more on reading voice tone and body language to figure out what people are saying to him. In this example, Mary’s voice tone, body language, and words told Robert that he had done something wrong and made him feel useless.

Factors That Affect Dressing

Dressing requires a multitude of abilities that includes fine motor skills, such as those needed for buttoning or fastening. It also requires gross motor skills like the ability to pull up trousers or pull down a shirt over one’s head. A person must also have the ability to discriminate what clothes are appropriate for the season, weather, time of day and occasion. Dressing requires memory of where clothes are located , as well as the ability to perceive the position of one’s arms and legs in relation to the garment. All of these abilities decrease as Alzheimer’s disease progresses.

A combination of additional factors associated with dementia can reduce the ability to dress oneself. This includes agnosia, or not recognizing objects or the environment; apraxia, which is the inability to automatically perform learned skills or connect what one intends to do with the actions needed to do it. Examples of apraxia include forgetting how to eat, dress, bathe, brush teeth, and walk. Dementia also causes a loss of organizational, planning and decision-making skills.

In one model of behavior, all behaviors are considered to be responses to stimuli in the environment. This model explains how people with dementia try to make sense of their world and do what is expected of them by reacting mechanically to stimuli in their environment. For example, if a doorknob is in front of them, they grasp it. If there is an open door, they go through it. Based on this principle, caregivers can increase the likelihood of getting a response by setting up stimuli in the environment for that response. On the other hand, caregivers can decrease the likelihood of a difficult behavior by removing stimuli that may lead to that difficult behavior

Case Study 2

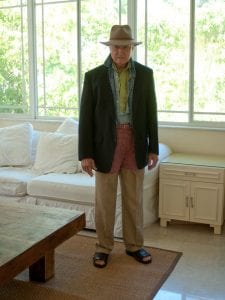

Here is a variation of the previous case study that shows how Mary might have handled the situation differently.

What might be happening in this situation?

- A) Mary had planned her day to accommodate unexpected delays and was not stressed about having to change Robert’s clothes.

- B) Mary affirmed Robert’s efforts to dress himself.

- C) Mary minimized the possibility of hurting Robert’s feelings by creating a positive scenario.

- D) All of the above.

Case Study 2 Answers:

Choice A: “Mary had planned her day to accommodate unexpected delays and was not stressed about having to change Robert’s clothes” is a good answer. Mary has learned to expect the unexpected. She could have also asked for help on the days that Robert showers, or made arrangements to have a family member come over to help with lunch and spend some time with Robert.

Choice B: “Mary affirmed Robert’s efforts to dress himself” is an excellent choice.

Affirming effort and accomplishment is important in maintaining one’s self-esteem. Due to the fact that people with dementia experience a loss of skills on a daily basis, caregivers should seek to provide them with frequent opportunities to reinforce their self-worth and self-esteem. To do this, caregivers should show appreciation when their care recipients make an effort to do things for themselves, even if the attempt is unsuccessful. Caregivers should also try to put their own worries and distractions aside in order to be positive, uplifting and truly engaged with their care recipients. Doing this will help to bring out the successes and positive aspects of the situation. Keep in mind that it is easier to keep a positive attitude if you take time to take care of your own health, feelings, and identity.

Choice C: “Mary minimized the possibility of hurting Robert’s feelings by creating a new scenario” is also a good choice. Mary used an important technique called distraction or redirection to help her get Robert to change his clothes. She redirected him from his mistake and hurt feelings by presenting the idea of wanting to see him in a “special” outfit. Mary also showed a smile and a positive attitude and used positive body language the whole time, which helped Robert forget about his negative mood.

Choice D: Because all of these answers are possibilities, the best answer is Choice D, “all of the above.”

Distraction or Redirection

Distraction or redirection is a technique that can be very useful for caregivers. Distraction includes changing the focus or introducing a positive image or subject to replace a negative one.

One of the signs of dementia is a decline in concentration and attention. Though a lack of concentration can make some activities difficult, it can also make it easier to transition someone from a frustrated or angry state to a calmer one using a smile, pleasant demeanor, and distraction. People with dementia might forget that they were frustrated or angry and simply move onto more positive things if they are properly distracted. Distraction can be a useful strategy for dealing with some difficult behaviors.

Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

One way of looking at assisting with activities of daily living or ADLs is to think of them as opportunities to spend more quality time with the person. Performing ADLs is basic to one’s sense of dignity, autonomy, and mastery. Loss of these abilities can lead to frustration, embarrassment and a sense of inadequacy. In addition, fear and frustration associated with ADLs are the source of most difficult behaviors. For these reasons, it is extremely important that caregivers approach ADLs with understanding and compassion, as this will go a long way toward preventing behavior difficulties and improving the quality of life for the caregiver and care recipient.

When assisting with ADLs such as dressing, caregivers should use an understanding and compassionate approach. Show patience, a sense of humor, and a positive attitude. Offer plenty of reassurance, positive affirmation, and never scold the person. It is important not to humiliate those with dementia with reminders that they need assistance. Instead, provide a positive atmosphere by using a calm tone of voice, an easy smile, and a sensitive, patient approach. People like to hear compliments about their appearance, so be generous with your compliments. And don’t forget that humor can help overcome and lighten a difficult or embarrassing situation.

Caregivers should take into consideration a person’s physical disabilities (such as weakness, fatigue, pain and joint stiffness) and sensory impairments (such as visual or hearing loss) when planning and assisting with ADLs. By adjusting and simplifying activities to the person’s abilities, caregivers can increase the likelihood of success. If handled well, caregivers can help those with dementia express their independence and build their self-esteem through ADLs.

It is important for caregivers to know and respect their care recipients and their personal preferences. Find out what their preferred routine is for dressing. This is referred to as person-centered care.

Person-Centered Care

Person-centered care focuses on the person. It considers their comfort and preferences and addresses unmet needs.

Agitation during dressing can occur when the caregiver is focused on the task rather than considering the comfort and preferences of the care recipient.

An important principle in any care-related activity is referred to as person-centered care as opposed to task-focused care. The behaviors such as agitation or combativeness need to be seen as expressions of unmet needs rather than oppositional behavior. Person-centered care considers the person’s history, feelings, preferences, abilities, strengths and needs.

If individuals become anxious and reluctant to get dressed, ask them (or try to determine from their body language) what might be frightening them or what they might need. They may need to use the toilet or may be having pain that is worsened by movement.

By gathering information and applying your knowledge about individuals, you empower yourself with the ability to create positive strategies that can enhance their quality of life.

Principles for Assisting with ADLs

Here are some general principles for assisting someone with activities of daily living, such as dressing.

Remember that an attractive appearance is important to self-esteem, and dressing is a great opportunity to promote autonomy and independence, and increase self-esteem for the person with dementia. Maximize individual abilities and minimize disabilities by encouraging self-care rather than doing the activity for them. Encourage people to use their remaining abilities by doing as much for themselves as possible while maintaining their safety and security. Reinforce effort and show appreciation by giving praise for both successful and unsuccessful efforts.

Because dressing is such a personal activity, caregivers need to allow individuals to do as much for themselves as they are comfortable and capable of doing. For example, caregivers should always offer to let the persons put on their own undergarments. If it is necessary for caregivers to assist with those things, they should always ask permission. One can say something like, “It’s time to put on your undergarments, is it alright if I help you put on your bra?” Give the person choices appropriate to the level of the person’s abilities, but not so many that they become frustrated. Examples of choices include what color sweater or skirt wear.

Provide cues and prompts for the person, but only when needed and without taking over. Offer reminders, such as the next step of an activity, if they seem to have forgotten. Also offer practical help. For example, help the person open and apply the toothpaste on the toothbrush, or place a comb in the person’s hand, as this may help cue the person to use it. If that doesn’t work, try demonstrating the step if necessary, as watching someone perform a task can sometimes prompt a person with dementia to imitate it. For example, comb your own hair if the person seems confused about what to do with a comb. Although it may be difficult to watch others struggle through an activity, it is better to let them try it and offer help only when they need it. So use hand-over-hand guidance only when necessary and with permission. Allow plenty of time for the activity. Do not rush, as the person can pick up on the emotional tone and feel frustrated.

Principles for Assisting with ADLs (Continued)

Use effective communication skills such as gaining eye contact, speaking clearly and slowly, and using familiar terms. You may need to repeat things and offer reminders. Say the important word last, as people are more likely to remember the last thing that is said. Break up activities into simple steps and give just one or two instructions at a time. For example, say, “Here is your shirt, please put it on.” Then say, “Here are your pants, please put them on,” as you hand each item to the person. In addition, observe body language for comprehension and comfort.

Adapt your instructions based on the functional and cognitive levels of the person, remembering that these levels may fluctuate. Plan the activity to allow the person to succeed by simplifying the steps to fit her or his remaining abilities.

Set reasonable expectations for appearance, as being too fussy about appearance will only add unnecessary stress to everyone involved.

Always insure the person’s privacy while dressing, making sure that doors are closed and blinds are drawn.

Provide adequate lighting in rooms, making sure that there is sufficient overhead lighting as well as good task lighting from a desk or floor lamp.

Make sure that there are no distractions in the room, such as noise, clutter, or other people.

Lastly, don’t argue or force the person to do something. If people remain insistent about choices that are not harmful to themselves or others, leave them alone. If changing their mind is important, try using distraction to move onto another topic. Then try the dressing activity again later when they may be more accepting of the idea.

Engage and Use a Relaxed Style

Now, let’s discuss how to engage someone and use a relaxed tone and style of instruction.

First, focus your attention on the person. When talking to individuals, face them, get their attention, and address them by their preferred names. Don’t assume that they like nicknames or terms like, “honey’ or “sweetie.” If you are hovering or talking with someone else while you are assisting your care recipient, your directions will not register with the person.

Use relaxed body language and tone of voice. Remember that the person may understand your body language better than your words, so smile and try to convey a relaxed, easy-going attitude. Use gestures and expressions to help communicate your message.

Give simple, step-by-step instructions that match the person’s level of understanding. Say the important words or instructions last, as this will make it easier for the person to remember.

Encourage the person to do as much as they can, even if that means simply cooperating with your caregiving efforts. Praise them for effort and cooperation. You can say things like, “You did a great job brushing your teeth. Your smile looks so bright with your clean teeth.”

Lastly, if you are assisting dressing, explain what you will do before each step.

Strategies for Assisting with Dressing

Here are some strategies for assisting someone with dementia to dress.

Persons with dementia have a decline in their ability to organize and plan, so try labeling drawers and closets according to the items that they contain. It is also helpful to lay out the clothes that they will wear in the order that they need to be put on. You can also hand one piece of clothing to the person at a time and help to put each piece on as needed.

Provide only a limited number of clothing options, offering simple choices, such as whether to wear the blue or the yellow shirt. Offering too many choices may cause frustration for the person.

Use layers of clothing, preferably with lightweight garments, as this makes it easier to remove or add layers as needed.

The disease and affected individuals are not easily predictable, so try to remain flexible when it comes to dressing. For example, if individuals refuse to change clothes for bed, consider letting them sleep without changing. After awhile, the clothes will more than likely feel uncomfortable, and the person will then want to change out of them.

If people consistently resist changing clothes, try scheduling the change at different times of the day when they may be more cooperative. For example, if someone resists changing into pajamas, try scheduling the change earlier in the evening when she or he is less tired.

Clothing Tips

Here are some tips for selecting clothes for those with dementia that are easier to manage.

First, provide clothes that are easy to put on and take off, such as clothes with elastic waistbands, fewer buttons, and fasteners on the front rather than the back. Simple, stretchable clothes are often easy to remove, so avoid clothes that are too tight or  complicated. For women, dresses are easier to manage than slacks when using the toilet. Slacks or skirts with elastic bands are easier to manage than those with zippers, snaps, or buttons. Velcro fasteners are the best choice for when fine motor skills decline.

complicated. For women, dresses are easier to manage than slacks when using the toilet. Slacks or skirts with elastic bands are easier to manage than those with zippers, snaps, or buttons. Velcro fasteners are the best choice for when fine motor skills decline.

Second, provide clothes that are durable and easily laundered. Delicate materials that can easily tear, or need dry cleaning can become costly.

Third, make sure that the person has properly fitting shoes and is wearing stockings or socks, as this provides more stability than slippers or bare feet. If the person has a strong preference for a particular item of clothing or a pair of shoes, try to have several of that item or style of item. This way the person will have something to wear if one has to be washed or discarded.

Dressing Challenges

Caregivers may encounter several challenges associated with dressing and clothing, as people with dementia often dress in unusual ways. This can include, the inappropriate layering of clothing, problems with disrobing, dressing for the wrong season or weather and refusal to undress or change clothing. There are many possible reasons for these dressing challenges, which the person with dementia may find difficult to communicate. Therefore, caregivers need to be perceptive about what might be causing the behavior and try to address any possible issues.

Let’s start by discussing the inappropriate layering of clothing. When people with dementia put on several layers of sweaters, skirts, or trousers, they may be doing this because they are cold and need more layers to feel comfortable. As people age, their bodies become less able to regulate temperature, which may cause older people to feel cold even when others find it warm. Keeping this in mind, caregivers should try to set a comfortable room temperature for the person and provide layers of clothing as needed.

Another dressing challenge that may arise includes problems with disrobing at inappropriate times. When this happens, it is important to find out the reason for this behavior, as it may be because they are warm or uncomfortable. Some common problems that cause discomfort include the garment being too tight or twisted, causing constriction. They may also need to use the toilet or have wet or soiled themselves. Another reason may be that they are confused about where they are, what time of day it is, or what they should be doing. If this happens, do your best to help reorient them to the present environment.

Another possible challenge is dressing in clothes that are not suited to the season or weather. For example, someone may put on heavy clothes on a hot summer day or a lightweight garment on a cold winter day. This is often caused by the person’s confusion about the season, weather, or location. If so, caregivers should remind the person about where they are and what season and weather is present. Another reason may be that the person cannot find the appropriate clothes. People may forget where certain clothes are located. There may be other reasons for the clothing choices, and caregivers should ask the individuals or try to figure out why they dressed as they did.

Refusal to Undress or Change Clothing

Sometimes people with dementia are reluctant to undress or change clothing, such as for bedtime or to bathe. When this happens, there is probably a reason for the behavior, such as fear that they will lose the garment or that it will be stolen. They may also be embarrassed or frightened to undress in front of others, or be afraid of being hurt or violated in some way. Another reason may be that they’re wearing their favorite clothes and do not want to change out of them.

To manage this issue, caregivers should try to find out the reason for the person’s refusal to undress or change clothes and address any issues. Begin by offering reassurance and using gentle persuasion rather than coercion. Do not pressure the person, as this may cause agitation or difficult behaviors. Allow the person to feel as though they remain in control.

It can be helpful to have in mind a list of reasons to explain why they should change their clothing. Some examples include getting ready for the day ahead, getting ready for bed, preparing for visitors, getting ready for a meal, or some special occasion. Another useful excuse is that it’s laundry day and the clothes that they’re wearing are dirty and need to be washed.

If the person still remains reluctant about undressing or changing, and the clothing choice is not harming the person or others, do not force the issue. Move on and consider raising the topic at a later time.

The Environment: Creating the Environment

Modifying the environment can make dressing a safer and more positive experience. The environment can be divided into two categories, the physical and human. The Physical Environment includes things like the actual space, the furniture and supports, lighting and temperature. While the Human Environment includes people and pets, which provide comfort, love, respect and autonomy to the care recipient.

Let’s begin with the physical environment. First, too many objects in a room can cause confusion, be distracting and increase the risk of accidents, so any clutter or obstacles should be removed. In addition, too much furniture, or too many rugs can cause injuries or falls, so simplify the environment by reducing unnecessary objects such as televisions, fans, free-standing heaters, power cords, and extra furniture. Finally, label and lock away harmful substances such as cleaning products.

Make sure the door locks can be opened from the outside. Or consider removing or disabling the locks, because people with dementia may lock themselves in a room and forget how to open the door. Also make sure that doors that lead outside are locked.

Falls are the leading cause of injury resulting in death among people 65 years and older, according to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. They are also the most common cause of nonfatal injuries and hospital admissions for trauma. There are many steps one can take to reduce the risk of falls. Make sure floors have a non-slip surface and are always dry. For example, place nonskid floor mats/bathmats on tile floors, or carpet floors using a single color, as carpet is safer and more comfortable for bare feet and will not produce glare.

Because many people reach for doors or door handles and furniture to steady themselves, it is important to have sturdy, stable furniture and doors or door handles to prevent falls.

As far as lighting goes, provide bright overhead and task lighting, as older people need more lighting than younger people in order to see properly. Reduce glare by using indirect lights and covering windows with light, sheer curtains. Lastly, try to use contrasting colors, as they are important for spatial orientation. Try to paint walls a flat color that contrasts with the color of the floors.

Providing Comfort

Now let’s look at the human environment. Because we have already discussed autonomy, we will now focus on how caregivers can create an environment that promotes comfort, love and respect. To promote a sense of comfort and security in someone with dementia, caregivers should do their best to provide a familiar and pleasant atmosphere. This starts with the people in the person’s daily life. A familiar caregiver with a pleasant, calm manner should assist the person with dressing. Surround the person with familiar, comforting objects, such as favorite photos, memorabilia, and flowers. Try playing calming music and using relaxing fragrances, such as lavender, Melissa oil (lemon balm), or mint. It is also important to provide good lighting, without glare or shadows that can confuse or frighten the person. A helpful tip includes covering mirrors, as people with dementia are often confused by reflections or not being able to recognize themselves. Caregivers should also follow simple, familiar routines for dressing. Clothing items should be organized and within easy reach so that the person is not confused. Also try to minimize the amount of time the person is undressed. If the person is undressed for more than a brief moment, cover any sensitive body parts with a robe, towel, or blanket.

The caregiver should also make sure that the temperature in the room is comfortable, as older people tend to chill easily. Other than temperature, caregivers also need to monitor for fatigue level, as fatigue and pain are frequent reasons for people to refuse dressing and it can be difficult for people with dementia to let others know that they are tired or having pain. Because of this, caregivers need to be perceptive and look for body language and other signs of fatigue or pain. If there are signs of pain or fatigue, you may need to take a break from dressing and address the source of their discomfort, or switch to an easier activity. Try to manage the person’s pain as fully and safely as possible, as pain can cause a person to feel fatigued, depressed, and/or irritable. If pain is often the cause of dressing challenges, you may want to consider giving pain medication prior to the activity as a preventive measure, taking into consideration that some pain medications can cause drowsiness or dizziness, which may increase the risk of falls or accidents. Consult a healthcare professional with any concerns.

Summary

In summary, dressing is important to a person’s sense of identity and self-esteem. Because of this, you should encourage individuals to do as much for themselves as they can and reinforce efforts at self-care by showing appreciation and giving praise. Never scold the person for mistakes.

Remain flexible and adjust to the persons’ abilities and needs, rather than your own. Keep reasonable expectations for performance and appearance. Simplify activities to their level of ability so that they will be likely to succeed and try to follow routines. Some examples of successful dressing routines include laying clothes out in the order that they should be put on, limiting choices, labeling drawers and closets according to the items they contain, providing clothing that is easy to put on and take off and is easily laundered. Set a comfortable room temperature for the person and provide appropriate layers of clothing when needed. If the person has a strong preference for a particular garment, try to have several of the same item or similar style of clothing.

To address challenging dressing behaviors, try to find out the reason for the behavior, address the issues and offer reassurance. Help orient people if they are confused and encourage them to change clothes only if necessary. Use persuasion, not coercion and do not pressure the person. Allow people to maintain a sense of control and offer some simple choices. Try to show patience, a sense of humor, and a positive attitude.

Lastly, to provide a safer environment for dressing, it is important to consider both the physical and human environments.

← Previous Lesson (Assisting with Activities of Daily Living: Bathing and Showering)

→ Next Lesson (Assisting with Activities of Daily Living: Grooming)

. . .

Written by: Catherine M. Harris, PhD, RNCS, and Mindy J. Kim-Miller, MD, PhD

Edited by: Sasha Asdourian

References:

- Bernick L, Nisan C, Higgins M. Care of the body: maintaining dignity and respect.Perspectives. 2002;26(4):10-4.

- Brawley, EC. How to improve the bathing experience. Alzheimer Care Quarterly. 2002;3(1).

- Connell, BR; McConnell, ES; Francis, TG. Tailoring the environment of oral health care to the needs and abilities of nursing home residents with dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly. 2002; 3(1) 19-25.

- Desai AK, Grossberg GT, Sheth DN. Activities of daily living in patients with dementia: clinical relevance, methods of assessment and effects of treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(13):853-75.

- Dougherty J MS, Long CO. Techniques for Bathing Without a Battle. Home Health Nurse. 2003;21(1):38-9

- Dunn JC, Thiru-Chelvam B, Beck CH. Bathing. Pleasure or pain? J Gerontol Nurs. 2002;28(11):6-13.

- Hoeffer, B; Talerico, KA; Rasin, J; et al. Assisting cognitively impaired nursing home residents with bathing: Effects of two bathing Interventions on Caregiving. The Gerontologist. 2006; 46(4) 524-532.

- Kovach CR, Meyer-Arnold EA. Preventing agitated behaviors during bath time. Geriatr Nurs. 1997;18(3):112-4.

- Mahoney, EK; Trudeau, SZ; Penya k, SE; & Macleod, CE. Challenges to intervention implementation: Lessons learned in the bathing persons with Alzheimer’s disease at home study. Nursing Research. 2006;55(26). S10-S16.

- Naik AD, Gill TM. Underutilization of environmental adaptations for bathing in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1497-503.

- Nami Kobayashi and Mariko Yamamoto.. Impact of the stage of dementia on the time required for bathing-related care: a pilot study in a Japanese nursing home. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004. 41(7): 767-774.

- Potkin SG. The ABC of Alzheimer’s disease: ADL and improving day-to-day functioning of patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14 Suppl 1:7-26.

- Rader, J; Barrick, AL. Bathing without a Battle. Alzheimer Care Quarterly. 2000. 1(4) 35-49.

- Rader J, Barrick AL, Hoeffer B, et al. The bathing of older adults with dementia: Easing the unnecessarily unpleasant aspect of assisted bathing.Am J Nurs. 2006;106(4):40-8.

- Rogers, JC; Holm, MB. Behavioral Rehabilitative activities of daily living. Alzheimer Care Quarterly. 2001;2(4) 66-69.

- Sloane PD, Hoeffer B, Mitchell CM, et al. Effect of person-centered showering and the towel bath on bathing-associated aggression, agitation, and discomfort in nursing home residents with dementia: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1795-804.

- Sloane PD, Rader J, Barrick AL, et al. Bathing persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 1995;35(5):672-8.

- Somboontanont W, Sloane PD, Floyd FJ, et al. Assaultive Behavior in Alzheimer’s disease: Identifying immediate antecedents during bathing.Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2004;30(9):22-29.

- Tetlow K. The dirt on bath design. Contemp Longterm Care. 1995-1996; Suppl:18-9, 21.