Welcome to the educational program Late Stages: Communication and Activities. This program will teach you about the changes in communication capacities that occur in the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease and provide some principles and strategies for communication. This program will also present principles and ideas for activities appropriate for individuals in the late stages of the illness.

. . .

This is Lesson 23 of The Alzheimer’s Caregiver. You may view the topics in order as presented, or click on any topic listed in the main menu to be taken to that section. We hope that you enjoy this program and find it useful in helping both yourself and those you care for. There are no easy answers when it comes to the care of another, as every situation and person is different. In addition, every caregiver comes with different experiences, skills, and attitudes about caregiving. Our hope is to offer you useful information and guidelines for caring for someone with dementia, but these guidelines will need to be adjusted to suit your own individual needs. Remember that your life experiences, your compassion and your inventiveness will go a long way toward enabling you to provide quality care.

Let’s get started.

Prefer to listen to this lesson? Click the Play button on the playlist below to begin.

Late Stage Communication

During the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease, problems with speech and understanding language increase considerably. Individuals may repeat questions and words over and over, they may contract several words into one to form nonsense words, and may even produce unintelligible sounds without a beginning or an end. It may be very difficult for a caregiver to know if a person is hungry, needs to use the toilet, or is in pain.

During the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease, problems with speech and understanding language increase considerably. Individuals may repeat questions and words over and over, they may contract several words into one to form nonsense words, and may even produce unintelligible sounds without a beginning or an end. It may be very difficult for a caregiver to know if a person is hungry, needs to use the toilet, or is in pain.

Here is where close observation of body language is important. Any utterance or gesture should be viewed as an attempt to convey meaning, and caregivers need to tune in to what the person is trying to communicate.

Let’s look at a case study about communication in the late stages of Alzheimer’s. Mary cares for her husband, Robert, who has late stage Alzheimer’s. In this scenario, she is preparing Robert for his bath.

Let’s look at a case study about communication in the late stages of Alzheimer’s. Mary cares for her husband, Robert, who has late stage Alzheimer’s. In this scenario, she is preparing Robert for his bath.

Mary: Robert, start taking your clothes off and put on this robe while I go and get a cup of coffee. When I get back, I’ll help you into the tub.

What was wrong with this interaction?- A. Mary failed to read Robert’s non-verbal message.

- B. Robert was being uncooperative by not following directions.

- C. Too many directions were given at once.

- D. Mary focused on the task rather than on Robert.

- E. All of the above.

Case Study 1 Answers:

Robert was gesturing toward the toilet and was probably trying to convey that he needed to use it. When people have difficulty making their needs known with words, they will use non-verbal ways of saying what they need. Robert was gesturing and making a throaty sound to get Mary’s attention, but it didn’t work because Mary was not tuned in to his non-verbal communication.

Choice B: Robert was being uncooperative by not following directions, is a possibility.

Because his needs were not being met, Robert could be angry with Mary and acting out by not cooperating with her instructions. This behavior is somewhat like a toddler who doesn’t get his or her way and drops the clothes on the floor rather than dressing.

Choice C: Too many directions were given at once, is also a good possibility.

Mary gave Robert four pieces of information at once without letting him respond, and then left him.

Persons in the later stages of dementia have low attention span and difficulty concentrating on a message or task. Robert probably could not sort out what he was supposed to do from all of Mary’s words.

Choice D: Mary focused on the task rather than on Robert, is another good answer.

Robert’s frustration could have been avoided if Mary had been “person-focused” with her care rather than “task-focused.” She appeared to be more concerned about getting the task of bathing underway and getting herself a cup of coffee than about Robert’s needs. Of course Mary’s needs also should be met, but this should be attended to before engaging with Robert.

Choice E: In this case study, all of the choices are good answers, therefore Choice E: all of the above, is the best choice.

Communication in Dementia

Let’s review the communication function and how it gets interrupted in Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

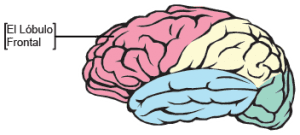

Two of the cognitive functions that are affected in Alzheimer’s disease are the abilities to speak and to understand. Technically, the total loss of speech is referred to as aphasia, whereas “dysphasia” is speech impairment, but not necessarily total loss. For simplicity, we will use the word aphasia to refer to the speech loss in dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease attacks places in the brain that control speech. Most of us think of speech as the words we are saying. But speech also includes receiving speech and being able to understand it. Making words is called “expressive speech,” whereas hearing and understanding words is called “receptive speech.” Expressive aphasia is sometimes seen in people who have suffered a stroke in the frontal lobe of the brain. The stroke has damaged part of the brain where speech is generated. The person may know what they want to say but the nerve pathways to the tongue, lips and jaw that have been badly damaged. Even though the muscles involved may work well, the words will not come out.

Alzheimer’s disease attacks places in the brain that control speech. Most of us think of speech as the words we are saying. But speech also includes receiving speech and being able to understand it. Making words is called “expressive speech,” whereas hearing and understanding words is called “receptive speech.” Expressive aphasia is sometimes seen in people who have suffered a stroke in the frontal lobe of the brain. The stroke has damaged part of the brain where speech is generated. The person may know what they want to say but the nerve pathways to the tongue, lips and jaw that have been badly damaged. Even though the muscles involved may work well, the words will not come out.

Persons with expressive aphasia have difficulty making their needs known, including their need to use the toilet, eat and drink, and treat any pain. By the late and end stages of dementia, persons may not even be able to produce word fragments and will make only moaning or groaning sounds.

Communication in Dementia (Continued)

It is easy to know if a person has difficulty speaking, but harder to know if they understand. Receptive aphasia means that a person cannot understand what they are being told. This can be a source of serious behavior problems in persons with dementia. If a person cannot understand what is being said, it can lead to frustration and anxiousness, especially if the caregiver speaks loudly or uses exaggerated mouth movements, which may be interpreted as scolding or anger. Some people may respond to apparent scolding with aggression or other inappropriate behavior.

The smaller red star represents the auditory cortex, or the part of the brain that actually “hears” what is being said. Often, the “hearing” part of the brain will not have much damage, so the person will be able to hear and even repeat what the caregiver says. However, Wernicke’s area, or the part of the brain where understanding occurs (represented by the larger red star) often becomes significantly damaged in the late stages of Alzheimer’s. Therefore persons may hear what is being said and even repeat the words, but cannot connect meaning to the words.

To deal with receptive aphasia, caregivers need to engage with the person, speak clearly and simply, use gestures and facial expressions, and say the important word last to help the person in understanding.

Even in the very late stages of the illness, when caregivers may wonder if individuals hear or understand anything, they need to speak clearly but gently, as it is difficult to know for sure what is being grasped.

Forms of Communication

There are many ways people communicate with each other. Verbal methods of communicating include words and utterances, such as moaning or crying. Non-verbal methods do not involve sounds, but rather, include all forms of body language, such as facial expressions, posture, gestures, and clothing choices. Whether one makes eye contact when speaking, how close one is positioned to someone, and whether one is in front, behind, seated, or standing over someone else are also part of conveying non-verbal communication.

There are many ways people communicate with each other. Verbal methods of communicating include words and utterances, such as moaning or crying. Non-verbal methods do not involve sounds, but rather, include all forms of body language, such as facial expressions, posture, gestures, and clothing choices. Whether one makes eye contact when speaking, how close one is positioned to someone, and whether one is in front, behind, seated, or standing over someone else are also part of conveying non-verbal communication.

Late Stage Communication

The loss of verbal abilities is progressive, and in the late stages of Alzheimer’s, it is not unusual for persons to have a total verbal vocabulary of 100 words or less.

Individuals may repeat words or phrases incessantly or echo what others say, use poor grammar and diction, and may speak only in jargon or make noises that lack apparent meaning. Often there is a total lack of coherent speech and verbal responses to directions or questions. Understanding of words is usually poor to non-existent. They may not even be aware that someone is speaking to them. They may no longer be aware of social interaction or expectations and may withdraw completely from any communication.

When persons with Alzheimer’s disease lose the ability to use words effectively, caregivers need to rely on the emotional and behavioral messages and body language to understand their needs. The use and understanding of non-verbal messages are retained much longer than words and sentences. Individuals in the late stages of dementia are often very capable of reading body language and facial expression as well as the voice tone of their caregivers. Caregivers need to cultivate their own non-verbal cues and clues and monitor their voice tone and inflection to be able to convey important messages. Non-verbal communication skills are valuable tools in providing care.

When persons with Alzheimer’s disease lose the ability to use words effectively, caregivers need to rely on the emotional and behavioral messages and body language to understand their needs. The use and understanding of non-verbal messages are retained much longer than words and sentences. Individuals in the late stages of dementia are often very capable of reading body language and facial expression as well as the voice tone of their caregivers. Caregivers need to cultivate their own non-verbal cues and clues and monitor their voice tone and inflection to be able to convey important messages. Non-verbal communication skills are valuable tools in providing care.

Emotional Expression

With diminished verbal abilities and memory problems, needs and worries are often expressed with emotions such as frustration, anger, sadness, and fear.

With diminished verbal abilities and memory problems, needs and worries are often expressed with emotions such as frustration, anger, sadness, and fear.

Behavioral Expression

Behavior is also a way that communication disabilities are expressed in the late stages.

Behavior is also a way that communication disabilities are expressed in the late stages.

Examples of behavior that result from inability to communicate include resistance to care, agitation, screaming, crying, wandering, combativeness, and withdrawal. Even when mobility decreases, some of these behaviors will continue into the late stage of the illness.

Retained Abilities

While individuals experience many losses as dementia progresses, it is important to remember that they also retain a number of abilities that have important implications for communication. For example, even very late in the illness, most still have self-awareness and sense of well-being or how they feel; they can experience and express a range of emotions, recognize emotions in others based on facial expressions, gestures, voice tone and behavior, and can express pleasure and displeasure. Caregivers can tap into and use these retained abilities as a way of establishing caring relationships, reducing tension, and establishing shared meaning.

While individuals experience many losses as dementia progresses, it is important to remember that they also retain a number of abilities that have important implications for communication. For example, even very late in the illness, most still have self-awareness and sense of well-being or how they feel; they can experience and express a range of emotions, recognize emotions in others based on facial expressions, gestures, voice tone and behavior, and can express pleasure and displeasure. Caregivers can tap into and use these retained abilities as a way of establishing caring relationships, reducing tension, and establishing shared meaning.

Guidelines for Communication

Here are some guidelines to consider in communicating with your person in the late stages of dementia. First of all, we need to take into consideration that most individuals with dementia are elderly and probably have some vision and hearing loss, and are easily fatigued. If they also have dementia, they will have a short attention span and difficulty concentrating on a task. Make sure that individuals have properly placed, functioning eye glasses and hearing aids if needed.

Here are some guidelines to consider in communicating with your person in the late stages of dementia. First of all, we need to take into consideration that most individuals with dementia are elderly and probably have some vision and hearing loss, and are easily fatigued. If they also have dementia, they will have a short attention span and difficulty concentrating on a task. Make sure that individuals have properly placed, functioning eye glasses and hearing aids if needed.

When initiating conversation, introduce yourself even though you have done so many times before. Sit close, make eye contact, and say the person’s name, using the preferred form of address, such as Robert, Dr. Miller, Captain Jones, or Mrs. Smith, as they prefer. Speak clearly in a normal tone of voice.

For conversation or important directions, find a quiet setting where noise and other distractions are minimal. Maintain a pleasant demeanor. Even late stage Alzheimer persons will perceive angry or stressed messages more readily than what is actually said. They will perceive these emotions and be frightened or worried.

Giving Directions

When giving directions, continue to speak softly, clearly, and slowly to give the person time to take in what you are saying. In referring to persons or objects, nouns are more easily understood than pronouns. For example, say “Robert, Sally is here to visit you during breakfast. Sally will help you with breakfast” rather than “Sally is here to visit you during breakfast. She will help with it.” Or, Robert, I have brought your wheelchair. Let me help you get into the wheelchair.” is more easily understood than “I have brought your wheelchair. Let me help you with it.”

When giving directions, continue to speak softly, clearly, and slowly to give the person time to take in what you are saying. In referring to persons or objects, nouns are more easily understood than pronouns. For example, say “Robert, Sally is here to visit you during breakfast. Sally will help you with breakfast” rather than “Sally is here to visit you during breakfast. She will help with it.” Or, Robert, I have brought your wheelchair. Let me help you get into the wheelchair.” is more easily understood than “I have brought your wheelchair. Let me help you with it.”

Saying the important word last, as in the word breakfast in the previous example, will be easier for the person with dementia to retain.

And, because of short attention span and difficulty with concentration, use simple directions and only one direction at a time.

The directions should be related to the task at hand and close to the time they need to be carried out. For example, say: Robert, it’s time to get dressed.” Then say “Now put your hand through this sleeve;” or “Now put on your hat.”

Give directions in a positive mode. For example, say: “Robert, please come into the dining room.” Rather than: “Don’t go into the kitchen.” Or if someone is doing something that she or he shouldn’t, such as walking out the door towards a potentially dangerous street, say something like: “Hi Robert. (pause) It’s a beautiful day.” Then gently take his hand and say: “Please come with me to the courtyard! (pause) We can feed the birds.” and direct the person away from the door and to the safe area for walking.

It also helps to use pleasant facial expressions, pictures, hand signals, and pantomime to convey your message.

Attending

Attending to someone means that you are paying attention to the person you are helping. It requires you to tune in to what the person is trying to communicate. Respect any attempt to communicate even if the facts and grammar are wrong. This will increase the person’s self esteem and sense of security. Be patient and wait for a response. It takes time for the individual in the late stages to process information and generate a response. Part of listening means not to talk while you wait for a response. Don’t interrupt or rush people if they seem slow to respond or you think you know what they are going to say. This will only throw off their concentration. By the same token, don’t correct them. This may only serve to embarrass and frustrate them.

Attending to someone means that you are paying attention to the person you are helping. It requires you to tune in to what the person is trying to communicate. Respect any attempt to communicate even if the facts and grammar are wrong. This will increase the person’s self esteem and sense of security. Be patient and wait for a response. It takes time for the individual in the late stages to process information and generate a response. Part of listening means not to talk while you wait for a response. Don’t interrupt or rush people if they seem slow to respond or you think you know what they are going to say. This will only throw off their concentration. By the same token, don’t correct them. This may only serve to embarrass and frustrate them.

Observe non-verbal messages and cues for receptive or non-receptive reactions. Focus on the emotional, non-verbal communication for meaning. This builds trust.

And, double check their message. Make sure you understand.

If persons digress or lose their train of thought, try repeating back to them the last words that they said to focus their attention back on track. Or summarize what was being said or ask appropriate questions to help them remember what they were trying to communicate.

If you don’t understand, it is usually appropriate to say so and ask the person to repeat or restate something.

If the individual does not appear to understand your directions, you can repeat or restate the direction.

However, if there are signs of frustration on the part of the person, it may be best to leave it and come back later when the timing seems better.

Empathy and Validation

A communication strategy that assists caregivers to work effectively with people with dementia involves conveying empathy and validation. The goal of this strategy is to affirm the person’s feelings behind the message rather than focusing on the content of the message. Remembering that all behaviors and emotions have meaning, the task for caregivers is to confirm what they believe the meaning to be. Using this strategy requires that caregivers carefully observe the emotions, behaviors and environment, and reflect back to the person what you believe is going on.

Here is an example of a caregiver, Sally, communicating with Robert, who has late stage dementia, using empathy and validation.

Empathy and Validation (Continued)

In this example, the caregiver observed that Robert was anxious and worried. She approached him and called him by the name that he prefers. Next she stated what she had observed, and asked what he was looking for. She then validated his emotional expression by stating that he looked worried, and then asked what he was worried about.

Focusing on the emotional content, the caregiver restated or rephrased Robert’s words, by saying “you are worried about being behind schedule fixing the engines for your customers.” Then, knowing that his attention span was short, she increased the focus on his history as a mechanic and garage owner to redirect his focus from finding his keys and going to the garage. This allows Robert to reminisce and increase his self esteem by reflecting on his successful career while reducing his anxiety.

Very Late or End Stage Communication

All of these communication strategies continue to apply into the very late and end stages of Alzheimer’s disease with a couple of modifications. First, closer observation will need to be made to body language the tone of vocalizations. Second, any touching needs to be more gentle. At this point in the illness, persons may be mute for words but may cry out, moan or use vocalizations with no attempt at forming words. It is extremely important to pay attention to the tone and context of these utterances, and to closely observe any facial expression and mouth movements. They may be conveying pain, hunger, thirst, or discomfort of some sort.

In the very late stages of dementia, touch is an excellent way of conveying caring and calming messages. However, because caregivers do not really know how much individuals are able to comprehend, permission should be verbally requested before touching, particularly of sensitive or private areas. It may seem that the person does not respond, but even a very slight, affirmative facial movement, such as a nod or smile, may be viewed as permission. It would be alright to proceed with the touch while paying attention to any tension in the body or other resistive response.

Here is an example.

Private Care Necessities

When it is time to clean someone after an episode of incontinence or a linen change is necessary, caregivers should also obtain permission or at least provide a “warning” of what is to take place.

When it is time to clean someone after an episode of incontinence or a linen change is necessary, caregivers should also obtain permission or at least provide a “warning” of what is to take place.

Family Communication

In these late stages, family members should also be encouraged to touch their affected loved ones and enjoy quality time with them. They can gently stroke their loved one’s arm, hold their hand, read to them, or just sit with them. It is not possible to know if there is awareness of a visitor’s presence, but the only approach is to assume that the person is aware of the presence of others.

In these late stages, family members should also be encouraged to touch their affected loved ones and enjoy quality time with them. They can gently stroke their loved one’s arm, hold their hand, read to them, or just sit with them. It is not possible to know if there is awareness of a visitor’s presence, but the only approach is to assume that the person is aware of the presence of others.

Spiritual Needs

As death approaches, people need gentle care and family close by. Attending to their spiritual needs through the family pastor or local priest, should be included in a hospice plan according to the wishes of the individuals and their families.

As death approaches, people need gentle care and family close by. Attending to their spiritual needs through the family pastor or local priest, should be included in a hospice plan according to the wishes of the individuals and their families.

Summary of Communication

In summary, Alzheimer’s disease causes changes in the brain that affect speech and understanding. In the late stages of the illness, expressive and receptive aphasias can make communication very challenging and result in behavioral and emotional expressions of frustration. Nonverbal forms of communication become more important as the disease progresses. As verbal communication is lost, nonverbal methods persist as a way to convey and understand meaning both by the person with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. Caregivers should observe carefully facial expressions, body language, and the tone and environment of utterances. It is important to take into consideration the person’s vision and hearing and the communication environment.

In summary, Alzheimer’s disease causes changes in the brain that affect speech and understanding. In the late stages of the illness, expressive and receptive aphasias can make communication very challenging and result in behavioral and emotional expressions of frustration. Nonverbal forms of communication become more important as the disease progresses. As verbal communication is lost, nonverbal methods persist as a way to convey and understand meaning both by the person with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. Caregivers should observe carefully facial expressions, body language, and the tone and environment of utterances. It is important to take into consideration the person’s vision and hearing and the communication environment.

Additional guidelines for maintaining good communication with someone in the late stages of dementia include giving simple, positive directions, attending to the person, using empathy and validation, careful listening and understanding, and using appropriate, gentle touch. Caregivers should continue to show respect for the person and convey a pleasant attitude.

Activities in the Late Stages

In this next section, we will discuss activities for people in the late stages if Alzheimer’s disease. No matter how advanced the illness is, incorporating meaningful and pleasurable activities into the daily schedule is an essential part of providing good care.

In this next section, we will discuss activities for people in the late stages if Alzheimer’s disease. No matter how advanced the illness is, incorporating meaningful and pleasurable activities into the daily schedule is an essential part of providing good care.

Activity-based Alzheimer care is based on the idea that any event, encounter or interaction with a family member or staff member, or any other diversional event is an activity. The purpose is to affirm the dignity of the person and provide pleasure and opportunities for success.

Planning Activities

Activities should be planned to recognize the person’s gender and generation interests, and tailored to the person’s beliefs, culture, life experiences and functional capacities.

Activities should be planned to recognize the person’s gender and generation interests, and tailored to the person’s beliefs, culture, life experiences and functional capacities.

All activities should show respect for the persons and affirm their dignity. They should have purpose and meaning to the individuals. Lastly, activities need to reinforce retained capacities, give pleasure and allow for success at whatever level of function.

Activities: Self-Care

Activities generally fall into three categories: Self or Personal care, productive, and leisure activities.

Activities generally fall into three categories: Self or Personal care, productive, and leisure activities.

Self-care activities include bathing, dressing, grooming, eating, drinking and toileting. When considerable assistance is required for personal care, caregivers can make it a social time by commenting on an item of clothing, the perfume of the soap, or the hair style. To make self-care activities more pleasurable, try singing a song, reciting a short poem or nursery rhyme, or talking about the person’s family while assisting with the activities. It is important that these activities be conducted with respect, reinforce retained capacities, and recognize personal preferences.

Activities: Leisure

A leisure activity can be any activity that provides pleasure. When a person is confined to a wheelchair, the number of leisure activities is diminished, but there are still some that can bring satisfaction and pleasure. For example, watching birds in an aviary or being wheeled around a garden and touching the flowers could bring pleasure as would watching a visiting children’s group sing and dance. Someone who has been a musician could listen to music or attend live musical performances.

Singing hymns and attending a weekly religious service would also reinforce spiritual values. Many people who have Alzheimer’s disease and do not seem able to speak will be able to sing, forming the words quite adequately.

Activities: Productive

Productive activities for someone in the late stages of Alzheimer’s could include folding towels or stirring batter for a cake or pancakes. Group activities can include people in late stage by assigning the simpler tasks to them. For example, if the group is making a cake, a higher capacity individual can add ingredients to the bowl, while someone with less capacity can simply be handed a spoon and invited to stir the batter. At an even later capacity, tasting the cookies or cake that others made is  still participating in the activity. Shelling peas or snapping beans is another activity that can afford some success even in the late stages. And that is the point, after all, to allow the individual to feel useful, successful and increase self esteem.

still participating in the activity. Shelling peas or snapping beans is another activity that can afford some success even in the late stages. And that is the point, after all, to allow the individual to feel useful, successful and increase self esteem.

Folding towels or napkins is a simple, productive activity for someone in more advanced stages of dementia. Place a pile of napkins at a table in front of the person, sit down at the table, and begin folding, smiling and making eye contact. Any effort to fold should be applauded, whether the napkins have to be folded again or if they fall on the floor and have to be re-laundered.

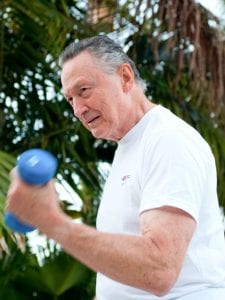

Physical Exercise

Physical exercise is an important activity and needs to be included even in late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. If the person is still able to walk, walking is an excellent form of exercise. For someone who is not ambulatory, exercising to music while sitting in a chair can be energizing and fun. Chair exercises can be vigorous or less so, depending on the individual’s capacity.

Physical exercise is an important activity and needs to be included even in late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. If the person is still able to walk, walking is an excellent form of exercise. For someone who is not ambulatory, exercising to music while sitting in a chair can be energizing and fun. Chair exercises can be vigorous or less so, depending on the individual’s capacity.

Even in end-stage Alzheimer’s, passive exercises are beneficial for breathing and circulation. An example of passive exercise would be for the caregiver to stand at the side of the bed, take the person’s arm by the hand and elbow and lift it gently up and down 2 to 3 times, then move it side to side 2 to 3 times, and then bend the elbow 2 to 3 times. This could be repeated with the other arm and both legs.

Care must be taken to observe the person for signs of discomfort or stress, such as tension in the muscles. The caregiver needs to judge the person’s capacity to tolerate the passive exercise and, of course, if the individual is in the last hours of life, comfort is the primary concern, and exercise is not appropriate.

Summary of Activities

In summary, incorporating meaningful and pleasurable activities into the daily lives of those with Alzheimer’s disease is an essential part of providing good care.

Activity-based Alzheimer care is based on the idea that any event, interaction, or diversional event is an activity. Activities can involve self care, productivity, or leisure that would be appropriate for someone in the later stages of the illness. Physical exercise is an important activity that can be modified to the person’s level of ability. All activities should respect the individuals and their personal preferences, affirm their dignity, give pleasure, reinforce retained capacities, and allow for success.

← Previous Lesson (Traveling, Driving, Holidays, and Special Occasions)

→ Next Lesson (Hospice and Bereavement)

. . .

Written by: Catherine M. Harris, PhD, RNCS (University of New Mexico College of Nursing)

Edited by: Mindy J. Kim-Miller, MD, PhD (University of Chicago School of Medicine)

References:

- Allen RS, Burgio LD, Fisher SE, Hardin JM, & Shuster JL, (2005). Behavioral characteristics of agitated nursing home residents with dementia at the end of life. The Gerontologist 45: 661-666.

- Bayles, K.A., Tomoeda, C.K., Cruz, R.F. & Mahendra, N. (2000). Communication abilities of individuals with late-stage Alzheimer Disease.Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 14 (3), 176-181.

- Bernick L, Nisan C, Higgins M. (2002). Care of the body: maintaining dignity and respect. Perspectives.;26(4):10-4.

- Boyd CO and Vernon GM. (1998). Primary care of the older adult with end-stage Alzheimer’s disease. The Nurse Practitioner. 23 4:63–83.

- Broton, M., & Koger, S.M. (2000). The impact of music therapy on language functioning in dementia. Journal of Music Therapy Association,37 (3), 183-195.

- Calkins M; Szmerekovsky JG; Biddle S. (2007). Effect of increased time spent outdoors on individuals with dementia residing in nursing homes. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 21(3-4): 211-28.

- Chalmers, J. (2000). Behavior management and communication strategies for dental professionals when caring for patients with dementia.Special Care in Dentistry, 20 (4), 147-154.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL and MacKenzie CR. (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies:Development and validation. Journal Of Chronic Disease.40(5):373–383.

- Eisdorfer C, Cohen D, Paveza GJ, et al. (1992). An empirical evaluation of the global deterioration scale for staging Alzheimer’s disease.American Journal of Psychiatry 149(2):190–194.

- Ekman, S., Norberg, A., Viitanen, M. & Winblad, B. (1991). Care of demented patients with severe communication problems. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 5 (3), 163-170.

- Ekman, S., Wahlin, T., Biitanen, M., Norberg, A., & Wiknblad, B. (1994). Preconditions for communication in the care of bilingual demented persons. International Psychogeriatrics, 6 (1), 105-120.

- Epps, C.D. (2001). Recognizing pain in the institutionalized elder with dementia. Geriatric Nursing, 22 (2), 71-77.

- Gleeson, M. & Timmins, F. (2004). Touch: a fundamental aspect of communication with older people experiencing dementia. Nursing Older People 16 (2), 18-21.

- Gotell, E., Brown, S., & Ekman, S. (2002). Caregiver singing and background music in dementia care. Western Journal of Nursing Research,24 (2), 195-216.

- Hoffman, SB & Kaplan M. (1996). Special care programs for people with dementia. Health Professions Press.Baltimore.

- Kim, W.J., & Buschmann, M.T. (1999). The effect of expressive physical touch on patients with dementia. International Journal Nursing Studies, 36 (1999), 235-243.

- O’Donovan, S. (1996). A validation approach to severely demented clients. Nursing Standard. 11 (13-15), 48-52.

- Paniagua MA; Paniagua EW. (2008). The demented elder with insomnia. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 24(1): 69-81.

- Prigerson, HG (2003). Costs to Society of Family Caregiving for Patients with End-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2003 Nov 13;349(20):1891-2.

- Sally Planalp a; Melanie R. Trost (2008). Communication Issues at the End of Life: Reports from Hospice Volunteers Health Communication.23(3):222 – 233.

- Zgola, J. (1997). Activity Based Alzheimer Care: Building a Therapeutic Program. The Alzheimer’s Association, Chicago, Ill.